The other day I posted a link on Facebook to an article I wrote about wine writer ethics. A friend I respect made a comment that said, essentially, “Enough about wine. Real people are struggling in the world.”

It led me to ask myself: Why do I write about wine?

First, it’s important to understand that I do not write about wine because I like to drink wine. Not that I don’t like to drink wine, of course. But I was drinking wine long before the thought of writing about wine appealed to me.

So why did that Facebook comment offend me so much? Why did I let it bother me when I could easily have ignored it?

The answer, I think, lies within my desire to make lasting contributions. And I’m not writing about wine because I can’t wait to taste the latest 95 pointer. I’ve suffered more existential crises in my life than most people twice my age. I am very often pondering my impact, or lack thereof, on society. It’s a rather vertiginous habit, by the way.

So let me be clear: If you think all wine writing is some kind of worship of hedonism, you’re wrong. If you think all wine writing is an ostentatious attempt to glorify luxury products, you’re wrong.

But of course, some wine writing is exactly what I just described. Some of it is the worst kind of back-slapping, trophy-chasing, handout-seeking pabulum. And on the rare occasions when the world’s most expensive wines have found their way into my glass, I confess to feeling giddy and grateful instead of dripping with cynicism. I’m not perfect. I’m as fascinated by a 30-year-old first growth as just about any collector.

All of that misses the point, however.

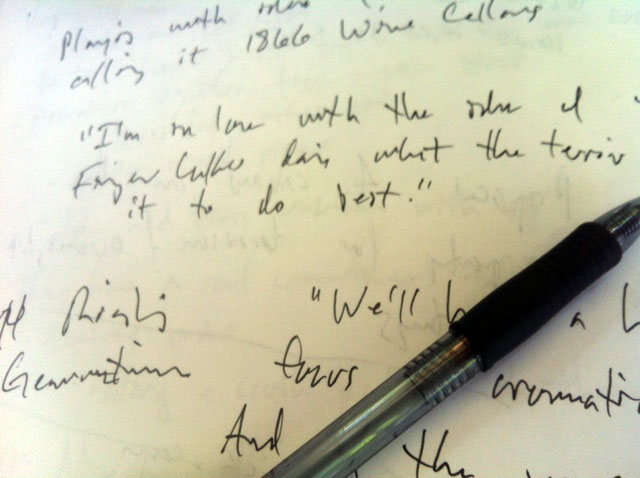

[pullquote_right]

[/pullquote_right]

We go through life building connections, then watching as some of our connections are frayed, then trying to rebuild what we’ve lost. We make friends but we move away. We promise to make time for something, but never do. And later we look back and struggle to recall the details of what once seemed so special. That can hurt. We lose our connection to people and places.

I have not found anything — not a drug, not a piece of technology, not a new-age technique — that can preserve connections like wine can.

This is true on many levels, the most obvious of which is a wine’s sense of place. You can purchase a bottle of X in a store, and you might get a sense for the land on which that wine was grown. But if you walk those rolling hills and comb through the cellars, you can go home with the land in your mind’s eye and the scent of the air stamped into your brain. Over time, you will begin to forget. Open a bottle that you picked up that day, and it all floods back to you. That, more than obsession with soil and whether a wine tastes like the dirt in which the vines live, is terroir. If you have only drunk wine purchased in retail shops, I can’t recommend enough that you get out and go to the source. Months or years later, the sensation upon opening that bottle will be so visceral it might frighten you momentarily. The details you’d lost return, and return in such sharpness that you feel transported.

A wine’s sense of time can be even more moving. Imagine that bottle you picked up in a small winemaker’s cellar in Barbaresco. Years later you’ll treasure the wine’s ability to bring you back to the place you found it. But there’s more: You might find yourself staring at the year on the label. You might say things to yourself that surprise you. “I was a different person then.” “That was before we bought the house.” “That was a month before Dad passed away.” “That was the first time I shared a bottle with my fiancee.”

Even a photograph is just a memory. We hold on to our pasts with great care, but we can’t hold on to all of it. But a bottle of wine is more than an image preserved; it’s an actual moment, still living and accessible. You can drink it in, literally, and you can drink in the time in which it was made. You can absorb a reality gone by. You can reacquaint yourself with what you thought was gone.

Or you can learn new things about a time before you were born. One of the most stirring bottles I ever opened was a 1966 Dr. Frank Riesling. It was made before I was born; I have no memory of the time. Until I came across that bottle, I could only read about what the Finger Lakes’ first winemakers had done. Then, suddenly, an opportunity arose to get a hold of an actual ’66, a bottle 44 years old. No, I wasn’t there next to Konstantin Frank when he put this wine together, but smelling the mature wine and drinking a glass gave me a new appreciation for what he had done. It was an echo, faint but real, of a different era. It was alive.

Do you see, now, why I’m so reluctant to open the last bottle — no matter what it is, or where it’s from?

Perhaps you still say, So what? It’s still just wine, after all. It’s a drink. People are suffering in this world.

And I reply that you’re right. I’m not certain my passion for this subject is the most effective use of my skills. I’m conflicted, more often than I’d like to be. When I read the work of, say, Nicholas Kristof, I feel small and unimportant and almost embarrassed. There are writers who are seeking the most oppressed, the most persecuted, and these writers are changing parts of our world. What the hell am I doing, writing about wine?

But wine is food, and food is life, and life is about the connections we make. It’s about the people we become and the people we touch in our brief time here. It is not about 97 points or 200% new oak or $100,000 an acre or high-powered consultants. Life is about beauty, large and small, experienced and shared — especially shared. Some wine professionals make piles of money, but most don’t. Most risk just about everything they have in pursuit of fleeting beauty, a brief glimpse of their small place in a sprawling world. We are so fortunate to be able to share those gifts around the world now, thanks to technology. And we can share the stories, and the beauty, and the connections that wine can foster. With each bottle and each story shared, we’re more connected. And the more connected we become, the stronger our society will become. No, wine is not going to save the world — despite the insistence of my good friend Jeremy Parzen. But it might make the people of this world understand one another just a bit better. That’s important. To me, anyway. I hope it is to you, too.