By Sasha Smith, NYC Correspondent

So it came to me on Tuesday night as I was chewing on a

mouthful of Vino Nobile di Montepulciano and trying to decide if I could call

the tannins both “firm” and “drying”: the Diploma is to wine what dressage is

to horseback riding – arcane, academic and interesting to an extremely small,

and extremely passionate, group of people.

This point is not lost on Mary Ewing Mulligan,

(from now on, MEM for short) who reminded us that we are “operating in some

never-never land” at arm’s length from the average drinker’s experience. I appreciate

the discipline and critical distance, of course – otherwise I wouldn’t be in

the class – but it borders on the obsessive. At some point, can’t we just drink

the wine and shut up about it?

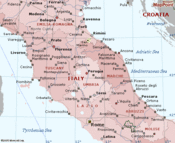

That being said, this week was one of our best lectures yet. Central Italy,

particularly Tuscany, is clearly near and dear to MEM’s heart. This is a woman

who has spent a lot of time in Chianti, and has a lot to say about it. I

particularly liked the observation she shared about Brunello di Montalcino, which

she picked up from a Tuscan wine merchant: with the best ones, you can feel the

tannins consistently from start to finish as you taste the wine – not just at

the back of the mouth. (I’m not sure how this works, physiologically, as I

think the sensors for tannins are near the middle/back of your mouth, but I’ll

take her word on it). Chianti and Sangiovese-based wines in general don’t rank

among my top ten, or even top twenty, reds, but Mary’s enthusiasm and knowledge

made me wonder if I need to re-evaluate my rankings.

Unfortunately, the wines we tasted kinda sucked. The Verdicchio was either

oxidized and/or over the hill. The Vino Nobile of the firm and drying tannins

was a 2003 and had some unappealing overcooked fruit aromas going on. Ditto for

the Montepulciano d’Abruzzo of the same year. We had a Brunello that Mary liked

quite a bit – a 2001 La Fornace – and that I recognized as a good wine, but didn’t

fall in love with. (Although I

did get the tannin from start-to-finish thing.) Which brings me to another tricky

part of the class: leaving your subjectivity at home. If a Pinotage shows up in

the tasting exam, I’ll have to put aside my intense dislike of the grape and

assess it on its own terms. And vice-versa for Rioja, a wine that I might evaluate too generously

because I like it so much.

My final discovery of the week is that my current study

method, filling out mega Excel spreadsheets on every region, is worthless. I

tried to use some of them to study for our first practice exam question, “Explain

the diversity in Burgundy’s white wines, when there is only one key grape variety” and they’ve been incredibly unhelpful.

Instead I’ve had to reread everything on white Burgundy in Jancis (we’re now on

a

first name basis.)

I have to email my essay off by tomorrow to an anonymous

grader in the UK who will then rip it apart and send it back with all kinds of merciless

comments, or at least that’s what I’ve been told. If they’re anything like the

exam graders, I’m in for a treat. As I wrote in my first post, WSET makes old

exams available, along with comments from the examiners. Here’s one of my

favorites:

“This [tasting note] is a classic example of someone who is seriously

underperforming in this examination. Whilst this candidate is clearly not

English speaking, it was not their lack of fluency that was the problem (in

tasting questions we are looking for accuracy rather than literary skills), it is their failure to use the Systematic

Approach to Tasting. This has resulted in vague, imprecise tasting notes with limited

potential for awarding marks.”

Or how about this classic:

“Questions on Eastern Europe are seldom popular, but quite often those who do attempt

them do well because it is their area of expertise. Sadly this was not the case

here with no candidates achieving distinction and only two with merit. This

question clearly divided those who knew about these regions and those who knew a

few basic facts about a couple of wines. In the case of the latter, many

scripts covered barely half a

side of A4 paper. This is seriously inadequate for this level of

qualification.”

I’m picturing the examiners as a combination between John Houseman in The Paper

Chase and the panel of judges at the end of Flashdance.

What a feeling, indeed.