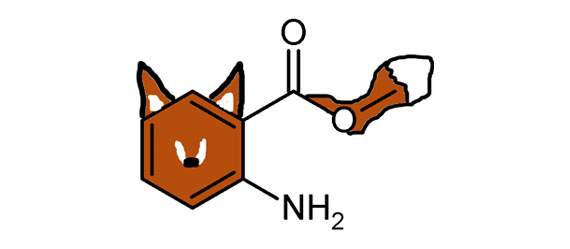

Artists' rendering of the methyl anthranilate molecule, responsible for "foxy" aroma in grapes and wine

By Tom Mansell, Science Editor

Interspecific grape hybrids (hereafter: hybrids) were initially bred in the late 19th century in response to

phylloxera, an American grape pest that migrated across the ocean to

Europe and began to decimate the less-resistant vinifera vines, almost

wiping out wine production. Since an American pest was the problem,

breeding vinifera with American vines was a potential solution (rather the American way,

eh? Screw something up halfway around the world, then try to fix it?),

and the result was original French hybrids like Seyval blanc, Baco

noir, etc.

Once it became evident that the hallowed vinifera vines

could be grown if grafted to American rootstocks (interestingly, also

often hybrids), hybrid vines quickly fell out of favor in France, and (partially because of a shoddily-done study involving malnourished chickens) some eventually were subject to a European Union-wide ban.

Nowadays in France and much of Europe, it's highly discouraged and in some cases illegal to make wines using hybrid grapes. Many hybrids have parentage of Vitis labrusca, a native American grape, and wines produced from some can have a "Welch's grape juice" (aka "foxy" aroma), highly disagreeable to the sophisticated French palate, of course. That doesn't mean that it's not done, though, and there are simple ways of finding out if hybrid grapes have been added to a wine.

Identifying hybrid characteristics

A key difference between vinifera and hybrids with American grape varieties is the way they synthesize their color compounds, called anthocyanins. In vinifera, the color compounds are usually found bound to a sugar molecule (glycosylated). This increases their stability and solubility in the wine. American varieties (and most hybrids therefrom) add two sugar molecules (diglycosylated). A simple test called TLC (thin layer chromatography) can be done on wine to determine if the anthocyanins have one or two sugars, and the presence of diglycosylated anthocyanin means the presence of hybrid juice.

A recent paper in the Journal of Food and Agricultural Chemistry

has identified the genetic reason for the lack of double sugar addition

in vinifera vines (a double mutation inactivates the protein

responsible, called 5GT). The authors also point out that the recently

discovered gene responsible for the synthesis of methyl anthranilate

(i.e., the principal "foxy" compound) is located very near the 5GT gene's location in the plant's DNA. The close proximity of these genes implies that they might go

together during plant breeding. Therefore, the relatively simple TLC test

for the 5GT gene could possibly be an indicator of foxiness in the

grape juice and could assist breeders in the future seeking to

eliminate methyl anthranilate.

Impact

Today, one of the most important reasons to grow hybrids in New York state is their cold-hardiness. Hybrid vines can weather a cold winter far better than many of their vinifera counterparts. Disease resistance is also a factor, as hybrid vines can be bred for and selected by their resistance to diseases like powdery and downy mildew, as well as root pests like phylloxera and nematodes.

These are great reasons, but some consumers simply can't get over the foxy aroma that many hybrids bring to the glass. Consequently, the ability to easily breed cold-hardy, disease-resistant hybrids that lack foxiness could be advantageous.

The market acceptance of hybrids is another story altogether and certainly not my area of expertise (for the record, I happen to like many hybrid grapes). Regardless of where you stand personally, there's no denying the economic impact of hybrids on New York state wine and on cool-climate wine regions in general.

Today, the science of genomics has opened doors to breeding possibilities beyond what Seibel and Baco could have imagined and there can be little doubt that hybrids will be at the forefront of the viticultural application of some of these technologies.