By Bryan Calandrelli, Niagara Region Editor

Niagara Ontario does not use the term “terroir” lightly. For a relatively new wine region, it has established one of the most detailed appellation and sub-appellation systems in the new world. Any serious discussion of winemaking in the region never fails to mention soil types, slope and proximity to Lake Ontario. And even though every grape in Niagara does have a unique origin, there are some wineries making terroir front and center – while at the same time employing specific methods in the vineyard and cellar to preserve their wines’ provenance.

As it happens, TasteCamp North attendees only had to wait five minutes before the weekend’s first speaker, Paul Bosc, Jr. of Chateau des Charmes, presented us with the map of Niagara’s regions and ten sub-appellations. For growers, owners and winemakers, this guide has become the holy book of terroir in Niagara.

Indeed, virtually every industry personality who spoke at TasteCamp began the discussion with a description and history of local soils, and even though dividing the region into “bench” and “Niagara-on-the-Lake or NOTL” wines is a gross oversimplification at this point, it was a good starting point. As the weekend went on, though, it became apparent, for example, that the there isn’t much similarity in the bench at St. David’s and the bench in Beamsville given the distance the bench is from the lake at both sites.

If anything, TasteCamp was a great reminder that making direct comparisons of any wines from different sub-appellations is helpful in discovering the diversity of the region, but is a strategy that must be approached with caution. Differences in vine age, clonal selection, vineyard spacing, trellising and cropping all contribute to the flavor and chemistry of the grapes. On top of that, the winemaker’s hand cannot be discounted when discussing the similarities and differences of wines produced from appellation to appellation.

Terroir as the Single Voice of a Vineyard

While there are several wineries featuring vineyard origins on labels locally, no other has based its identity on single vineyards more than Le Clos Jordanne. The winery focuses on chardonnay and pinot noir exclusively, with the goal of expressing the terroir of its four vineyards through these grapes. Le Clos Jordanne has three tiers of wines, with the first and least expensive being the Village Reserve. Simply put, any grapes that do not make the cut from LCJ vineyards go into this blend. Year to year, this blend is $25 and is all Niagara in style.

Le Clos Jordanne has three tiers of wines, with the first and least expensive being the Village Reserve. Simply put, any grapes that do not make the cut from LCJ vineyards go into this blend. Year to year, this blend is $25 and is all Niagara in style.

The next tier is the winery’s single vineyard bottlings, Le Clos Jordanne, Claystone Terrace, La Petite Vineyard and Talon Ridge Vineyard. These wines are all given native fermentations, with long, cool ferments and similar oak programs, ultimately with the goal of identical vinifications producing four distinctive wines.

The winery’s highest-priced bottling is their Le Grand Clos, which is the very best it has to offer in a given vintage. Ever since LCJ started making the Grand Clos Pinot Noir it’s come from the same block of the same Le Clos Jordanne Vineyard. What’s so special about this one spot?

“It’s actually more silty than the rest of the vineyard,” says winemaker Sebastien Jacquey. In my mind there’s nothing less sexy and less marketable than silt, so it’s ironic that the winery’s flagship luxury wine is from that site.

But that’s the point of the LCJ anyway: to isolate those small areas that produce the most distinctive wines. Unfortunately, though, TasteCamp attendees didn’t get to taste full horizontal flights of pinot or chardonnay. Although the 2008 Claystone Terrace Pinot Noir was enough to satisfy me.

Terroir Through Biodynamics and Wild Fermentations For a region that sees such cold temperatures in the winter, excessive moisture and humidity during most of the growing season and the ever-growing threat of unpredictable weather, the notion that biodynamic practices can succeed here isn’t one you’d hear from many unless you’re talking to Ann Sperling, winemaker at Southbrook Vineyards, in NOTL.

For a region that sees such cold temperatures in the winter, excessive moisture and humidity during most of the growing season and the ever-growing threat of unpredictable weather, the notion that biodynamic practices can succeed here isn’t one you’d hear from many unless you’re talking to Ann Sperling, winemaker at Southbrook Vineyards, in NOTL.

Sperling, like many who practice biodynamics, is convinced that the proof of its success is in the grapes and how her wines reflect where they are grown.

“Our viticultural practices give us ripe fruit, small berries and thin skins so in the winery we can be very gentle,” Sperling said during an interview I had with her last fall. “We don’t add any nutrients because we don’t need them.”

(The addition of yeast nutrients is a common winemaking practice that feeds the yeasts encouraging a healthy fermentation and reducing issues like volatile aromas, sulphur aromas and stuck ferments.)

Southbrook also has a clean record of using indigenous yeasts and indigenous maloactic bacteria in fermenting its wines. While there’s an obvious correlation between the philosophy of organics, biodiversity and native-yeast fermentation, Sperling thinks it goes well beyond that. She believes that the absence of synthetic fungicides preserves populations of the natural yeasts while not selectively destroying or encouraging the growth what occurs naturally in the vineyard.

Southbrook’s site has flat, features moderately vigorous soils and is far enough from Lake Ontario to warm up quickly in the spring, making it particularly suited to Bordeaux varieties. Crops are kept below two tons per acre and vines are generally not hedged. In the winery, fermentations are kept relatively cool reducing over extraction, and fining, filtration and new oak are kept to a minimum.

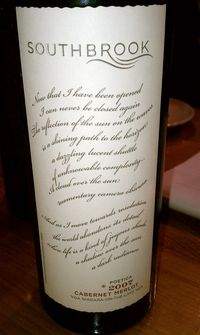

Friday night’s dinner at Ravine Vineyard featured a few selections from Southbrook including their 2005 Poetica Chardonnay, 2008 Whimsy Cabernet Franc and my favorite, their 2007 Poetica Cabernet Merlot. In my opinion, each of them showed enough restraint with oak and extraction to express the NOTL character.

Terroir By Gravity Flow and Gentle Winemaking

Not only is Niagara blessed with the soils and climate to make distinctive wines, it’s also blessed with people and the resources to make wines that highlight them. Tawse Winery strives for a natural balance in the vineyard and has the ideal facility to produce wines in a way that handles the grapes and wine in the most gentle and effective way.

The idea behind gravity flow wineries is simple: Limit the amount of stress, oxygen and physical manipulation of grapes, musts and wines using a well thought out construction that uses gravity to transfer wines throughout each phase of production.

The idea behind gravity flow wineries is simple: Limit the amount of stress, oxygen and physical manipulation of grapes, musts and wines using a well thought out construction that uses gravity to transfer wines throughout each phase of production.

Tawse’s Paul Pender gets to make wines in what is probably the closest thing I’ve ever seen to a wine production utopia. As esthetically pleasing as the winery is from the outside, to anyone interested in winemaking, what goes on behind the scenes is even more impressive.

From a crane inside the crush pad of the winery, the grapes (for reds) are and juice (for whites) is moved into primary fermentation vats at the highest level of the winery. The red grapes are only destemmed without any intentional maceration, leaving whole berry grapes for a cooler, longer fermentation.

Whites are also given delicate treatment starting at the crush pad. “We average 8-10 hours for pressing our whites…some wineries may only take two hours to press,” noted Pender.

Tawse keeps stainless tanks for the wines to settle out on next level downward. Without using pumps, the wine is simply allowed to flow through hoses down to this level and then ultimately down to one of the two impressive barrel cellars the winery built. The cellar is buried under several feet of earth to naturally maintain a constant temperature.

The cellar itself looks like what you’d see if you are lucky enough to visit the great estates of Bordeaux – until you notice the modern system of hoses and pipes in the ceiling that are used to move wine into the barrels. It’s truly an amazing setup.

All of this talk of winemaking would be a waste of time if the wines weren’t spectacular. The chardonnays poured at TasteCamp were both top notch, showing exactly the differences Pender hoped would come through in the side-by-side of Quarry Road and Robyn’s Block 2009 bottlings. My favorites at the bar were the Pinot Noir Cherry Ave 2008 and the Cabernet Franc Van Byers 2008.

Tawse wines show a tension while young that stand out more than most. While there’s no doubt that their intensive vineyard practices are giving them quality grapes, I think the unobtrusive methods practiced at the winemaking end are producing wines with better structure, purer fruit and less astringency than most, leaving a clearer taste of where they are from.

In the End

There are going to be plenty of assumptions, assertions and proclamations from our weekend in Niagara like cabernet franc does better in NOTL or riesling is better on the bench. Our experience at TasteCamp did not provide us with a complete picture of the region’s diversity in terroir and to be honest, it wasn’t supposed to. We would surely need more than the time we had.

With the sub-appellation system being less than ten years old, the benefits of the categorization are only now starting to show in the wines we tasted. Finding the right soil for the right grape is only the beginning. Then it becomes the right clone, the right spacing, the right trellis, the right cropping, right vinification. It goes on and on.

In the meantime, though, I need to decide which Niagara cabernet franc I want to drink next. Will it be the Lincoln Lakeshore from Tawse, a NOTL selection from Southbrook, a Niagara Escarpment wine from Vineland? Or maybe it’ll be a St. David’s Bench bottle from Chateau des Charmes or the Four Mile Creek from Coyotes Run. In my opinion they’re all pretty darn good.

We've had to reschedule it a couple times, but today

I'm excited to announce the third in a series of

We've had to reschedule it a couple times, but today

I'm excited to announce the third in a series of

Recent Comments