“The Hardest Things to Do Are the Ones That Matter Most”: Winemaking Lessons from TasteCamp

By Julia Burke, Beer Editor

Like every TasteCamp attendee, I’m a wine lover, but I’m also a beginning home winemaker with a personal interest in discovering what it takes to make world-class wine in my home region of Niagara. This means that in addition to tasting as much wine as I can, I take every opportunity to pick the brains of the winemakers — and occasionally harass them with samples of my own wine after battering them with questions.

I figure, when else will I get the chance to speak one-on-one with brilliant and talented people who have built their reputations on making amazing wines in the region where I hope to spend my life?

With that perspective, although the entire TasteCamp weekend was an amazing learning experience for me, a few particular interactions over the weekend had a special impact.

Lesson 1: Just Do It

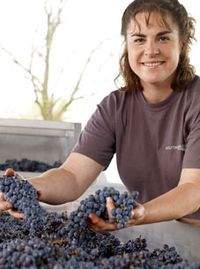

One was meeting Andrea Glass, winemaker at Good Earth Food and Wine Co. (Photo credit: Suresh Doss), at the grand tasting at Vineland Estates on Saturday. I had to wonder if I was on Candid Camera when I sipped her delicious cab franc rosé, loved it, found out she was the winemaker, and couldn’t resist asking her age. “I’m 24,” she replied. She's exactly my age and already a professional winemaker in Niagara.

One was meeting Andrea Glass, winemaker at Good Earth Food and Wine Co. (Photo credit: Suresh Doss), at the grand tasting at Vineland Estates on Saturday. I had to wonder if I was on Candid Camera when I sipped her delicious cab franc rosé, loved it, found out she was the winemaker, and couldn’t resist asking her age. “I’m 24,” she replied. She's exactly my age and already a professional winemaker in Niagara.

I couldn’t contain my excitement. Fortunately, Glass was a good sport and allowed me to barrage her with questions about her winemaking background.

A fifth-generation farmer, Glass studied viticulture and winemaking at Niagara College, and loaded up on harvest experience with vintages in Argentina and California as well as Niagara. The back-to-back continent-hopping vintage experience is something I’ve always wanted to do, especially after my two harvest stints in South Africa, and Glass couldn’t say enough about the practice. “I was able to cram eight years of experience into four years that way,” she explained. She advocated the combination of winemaking and viticulture courses, which have the key advantage of teaching students how to respond to unforeseen winemaking challenges instead of just addressing them as they occur, with real-world experience in varied conditions and climates.

I was humbled by Glass’s accomplishments at such a young age, impressed by her wines, and inspired to live in a region where a winemaker can make a name for herself so early in her career (without being the owner’s kid). I will be sure to follow developments at Good Earth from now on and hope to make a visit on my next trip across the border.

Lesson 2: Support Is Out There

After a day of tasting some of the most renowned Niagara-on-the-Lake producers to kick off TasteCamp, we headed to Ravine Vineyard for a cozy family-style dinner setup and presentation from consulting winemaker Peter Gamble and Southbrook winemaker Ann Sperling (Photo credit: Southbrook Vineyards). One of the great “power couples” of the wine world, Sperling and Gamble have between them an amazing background of experience in Niagara and internationally, and it was a treat to get their insights on the Niagara region in an informal, wine-focused event.

After a day of tasting some of the most renowned Niagara-on-the-Lake producers to kick off TasteCamp, we headed to Ravine Vineyard for a cozy family-style dinner setup and presentation from consulting winemaker Peter Gamble and Southbrook winemaker Ann Sperling (Photo credit: Southbrook Vineyards). One of the great “power couples” of the wine world, Sperling and Gamble have between them an amazing background of experience in Niagara and internationally, and it was a treat to get their insights on the Niagara region in an informal, wine-focused event.

To me one of the most interesting and unique aspects of the couple’s role in Niagara is their affinity for helping start-ups and existing growers and wineries work toward achieving organic and biodynamic certification. The process may seem an insurmountable challenge in a climate where frost, moisture, and cold weather are constant threats, but Gamble and Sperling explained that the rewards of organic and biodynamic practices are too obvious — and practical — to ignore. Not content to reap these rewards themselves, the team is passionate about spreading the love and acting as resources for others.

While introducing her Southbrook wines, Sperling explained that she has been guiding her partner growers through the bureaucracy and challenge of certification. “We hope to nurture and bring along other vineyards into [organic growing] and in 2010 we did help a grower get certified. We have another grower who has been growing organically but hasn’t done the paperwork, so we’ll help him get underway with that so we can add more acreage to the area that’s being organically farmed,” she said.

For Sperling, biodynamics is partly a question of promoting a healthy working and living environment. “We chose to farm biodynamically partly because it’s where we spend our life, and where we employ people and they spend most of their life and working hours, and so we wanted to create an environment that was as healthy as possible.” But it’s not just about health. Sperling is firm in her conviction that a biodynamically grown wine is a better wine. “We also do it for the high quality wines that we feel that we can make,” she said. “For us quality is an expression of site and terroir, and a vine that is raised biodynamically is very in tune with its locale and we feel that it presents the most truthful or best expression of the terroir and I think we’re seeing that in the wines that we’re producing,” she added.

Lesson 3: Trust the Vineyard

Gamble brought up the issue of vintage variation, which seems to be near and dear to the hearts of many in the soul wine (yes, I’m putting it out there; I’m sick of the arguments about the term “natural wine” so I’m hoping “soul wine” will catch on) movement.

The idea that a wine should express not just its soil, climate and other geographical characteristics but also the season in which its grapes were grown is an important conviction in this era of mass-produced big-brand wines, and it’s a point of pride for many cool-climate growers. Gamble told a story from the notoriously challenging 2009 vintage to illustrate the importance of seasonal voice — and of trusting the vines to express it.

“We always harvest on taste,” he said. “We pay attention to pH, TA, the relationship between tartaric and other things, but the bottom line is you go by taste. In 2009, a really difficult, very cool, challenging year, we didn’t harvest till somewhere in the first week of December—we didn’t like the flavors on the Bordeaux varieties until then. I had to explain it: Why are we suddenly 14-14.5 percent alcohol on the cab, whereas in big years we’re doing it at 13 percent? It’s totally based on flavors and it’s really amazing that when you’re up in the vineyard when you look at numbers—what pH do you harvest at, etc.—but taste is one of the things that tends to bring the unanimity among winemakers. Taste comes first and foremost,” she said.

Brian Schmidt of Vineland told a similar story on Saturday, in a discussion of vineyard yields. He decided to drop his crop to around 2 tons per acre, after the vineyard had been comfortably producing about 4 tons per acre from one year to the next. “The berries were bloated, fat, waterlogged, and I checked and it came in at 3.8 tons per acre,” he chuckled. “I tried, but the vineyard said, ‘no, actually, we’ve got this. We know what we’re doing.’” It was a great lesson in trusting a healthy vineyard rather than arbitrary numbers. A bit of a control freak myself, I took this message to heart.

Lesson 4: The Hardest Things To Do Are the Ones That Matter Most

My question for Gamble after the event was this: What is the most powerful argument or evidence that ultimately pushes growers and winemakers to take the plunge into organic/biodynamic viticulture despite the challenges?

As I suspected, the answer was that the proof was in the pudding — or rather, the pinot. “Quite awhile ago, maybe fifteen years, people in Dijon started with a particular section of a premier cru in Burgundy,” Gamble explained. The two side-by-side sections of pinot noir were tended by the same grower with the same methods—but in one section they used conventional leaf spray. “Rather than study the effects on the grapevine, they studied the final wine,” says Gamble, “and they were unanimous confirming the flavors. It’s one of the things that rarely gets discussed, the issue of flavors, but they did a blind tasting and word sort of got around that the flavors of the wine were better.” This ruffled some feathers, for obvious reasons. “One of the major spray producers decided to commission another university to retest with ‘more scientific conditions’… the word was that they got the exact same results,” Gamble says, “so the paper was never released.”

For Gamble that story sums up the ultimate motivation for going organic. “That’s it for me,” he says. “I always make a point of telling prospective proprietors that the hardest things to do are the ones that matter most.”

Wise words whether the topic is winemaking or life. Thanks to these and other fascinating conversations over the course of the weekend, I came away from TasteCamp more inspired than ever to keep making wine in Niagara. Tasting the world-class, terroir-driven wines (especially the cabernet francs, which I found the most exciting of anything I tasted) and getting a glimpse inside the heads and hearts of these industry movers and shakers was the best motivation I could imagine.