Yarrow flowers matured in a stag's bladder -- Preparation 502

By Tom Mansell

All images courtesy of The Millton Vineyard, Poverty Bay, NZ.

"For there is a hidden alchemy in the organic process." - Rudolf Steiner, Agriculture

At the heart of biodynamic farming are the famous preparations. In this post and the next post, we'll look at the contents of the preparations and their proposed effects and mechanisms or lack thereof.

This week's post will focus on the preparations added to biodynamic compost.

Compost Preparations

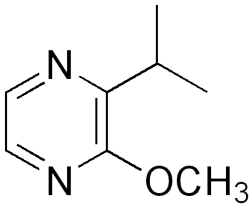

| Preparation |

Main Component |

Fermented in... |

Proposed function (Steiner) |

Proposed function (Josephine Porter Institute website) |

| 502 |

Yarrow blossoms |

Bladder of a stag |

"Its homeopathic sulfur content, combined in a truly model way

with potash, not only works magnificently in the plant itself, but

enables the yarrow to ray out its influences to a greater distance and

through large masses." |

Permits plants to attract trace elements in extremely dilute quantities for their best nutrition. |

| 503 |

Chamomile blossoms |

Cow intestines

|

"...has sulphur in the precise proportions which are necessary to assimilate the potash...assimilates calcium in addition. Therewith, it assimilates that which can chiefly help to exclude from the plant those harmful effects of fructation, thus keeping the plant in healthy condition."

|

Stabilizes nitrogen (N) within the compost & increases soil life so as to stimulate plant growth. |

| 504 |

Stinging nettle shoot |

N/A

|

"A jack of all-trades... It carries within it the element which incorporates the Spiritual and assimilates it everywhere, namely, sulphur....Moreover, the stinging nettle carries potassium and calcium in its currents and radiations, and in addition it has a kind of iron radiation."

|

Stimulates soil health, providing plants with the individual nutrition components needed. "Enlivens" the earth (soil). |

| 505 |

Oak bark |

Skull of a domestic animal

|

"The calcium structure of the oak rind is absolutely ideal....[Calcium] restores order when the ether-body is working too strongly, that is, when the astral cannot gain access to the organic entity."

|

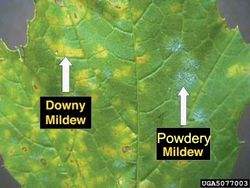

Provides healing forces (or qualities) to combat harmful plant diseases. |

| 506 |

Dandelion flowers |

Mesentery (gut lining) of a cow

|

"[i]t mediates the silicic acid finely, homeopathically distributed in the Cosmos, and that which is needed as silicic acid throughout the given district of the Earth. Truly this dandelion is a kind of messenger from heaven."

|

Stimulates relation between Silica (Si) and Potassium (K) so that Silica can attract cosmic forces to the soil. |

| 507 |

Valerian extract |

N/A

|

"...stimulate [the compost] to behave in the right way in relation to what we call the 'phosphoric' substance."

|

Stimulates compost so that phosphorus components will be properly used by the soil. |

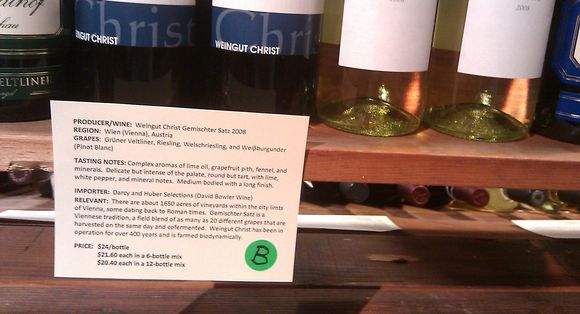

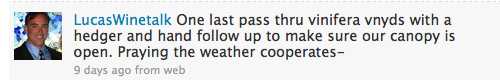

The preparations (that's 503 at right) are usually placed directly into the compost pile in small amounts, typically 5-10 grams or less for the solid mass, though they can sometimes be sprayed in the field in addition.

The preparations (that's 503 at right) are usually placed directly into the compost pile in small amounts, typically 5-10 grams or less for the solid mass, though they can sometimes be sprayed in the field in addition.

In his fifth lecture on agriculture, Steiner argues that the nitrogen content of biodynamic compost is improved by transmutation of elements such as potassium and calcium into nitrogen by organic processes.

"I know quite well, those who have studied academic agriculture from the modern point of view will say: "You have still not told us how to improve the nitrogen-content of the manure." On the contrary, I have been speaking of it all the time, namely, in speaking of yarrow, camomile [sic] and stinging nettle. For there is a hidden alchemy in the organic process. This hidden alchemy really transmutes the potash, for example, into nitrogen, provided only that the potash is working properly in the organic process. Nay more, it even transforms into nitrogen the limestone, the chalky nature, if it is working rightly."

This represents a misunderstanding of the nature of chemical elements, even by 1924 standards. The supposed phenomenon of biological transmutation, or the conversion of an element to a different element via a biological or organic process, quite simply violates the laws of physics.

It's important to note, though, that just because Steiner was a bit off in his explanation of the phenomena doesn't mean that these compost preparations have no effect at all. Many researchers have explored the effects of biodynamic agriculture, but until recently, these studies either compared conventional and biodynamic agriculture or lacked the statistical rigor required to make definitive conclusions. However, in the past decade or so, some intrepid researchers have taken a scientific approach to experimentation with the biodynamic preparations in an effort to gauge their efficacy and usefulness for modern farmers.

A review of peer-reviewed research into the effects of biodynamic preparations

One of the premier researchers in the compost field is Dr. Lynne Carpenter-Boggs, Biologically Intensive and Organic Agriculture (BIOAg) Specialist at the Washington State University Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources (CSANR) and an affiliate Assistant Professor in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences. She has been an author on several peer-reviewed papers comparing the effects of agriculture using biodynamic preparations to organic agriculture.

Washington Com-post

A 2000 study published in Biological Agriculture and Horticulture showed some differences in compost quality between

biodynamic and organic compost. The biodynamic compost had a

consistently higher temperature and 65% more nitrate (likely due to

aerobic nitrifying bacteria, not transmutation...) than the organic

compost. In addition, phospholipid fatty acid analysis gave different

results for biodynamic compost, suggesting that the microbial makeup differed slightly.

Also in 2000, the same authors published a study in the Soil Science Society of America Journal which sought to evaluate the differences in soil treated with organic or biodynamic compost. The authors also compared the results of composted soils to soils supplemented with mineral fertilizers. Over the many parameters measured, compost was shown to beneficial to soil quality, but no significant differences were found in any parameters between organic and biodynamic compost.

From the conclusions section:

"The soil biological parameters tested indicated many differences between soils that had received compost additions and those that had not. Both biodynamic and nonbiodynamic composts increased soil microbial biomass, respiration, dehydrogenase activity [an indicator of microbial activity], MinC [an indicator of available carbon], earthworm population and biomass, and qCO2 [microbe respiration]. No differences were found between soils fertilized with biodynamic vs. nonbiodynamic compost."

Does it translate to plants?

Wheat

In 2010, Dr. Jennifer Reeve, Assistant Professor of Organic and Sustainable Agriculture at Utah State University and a former student of Dr. Carpenter-Boggs, was the lead author on a study of biodynamic compost and its effect on wheat seedlings.

In this case, the compost contained grape pomace, which would be a readily available source of compost from wineries. The authors tracked compost parameters like the 2000 studies and found evidence of increased dehydrogenase activity, which indicated increased microbial activity in the biodynamic compost.

In addition, wheat seedlings were fertilized with the different composts. According to the paper, "In 2002, wheat growth with BD compost extract or BD compost extract plus fertilizer was always greater or the same as wheat growth with the control compost under the same conditions....Wheat growth in 2005 was similar

between BD and untreated compost showing that possible differences as a

result of BD treatment are not consistent year to year. Whether or not

any small differences as a result of BD compost preparations would

incur a practical benefit to the grower needs to be further

investigated." Seedlings treated with either compost extract had higher shoot height and biomass and root biomass, confirming the beneficial effect of compost in general.

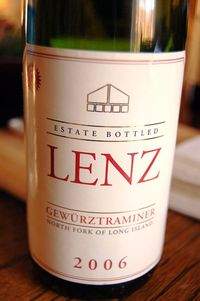

Okay, fine for wheat, but this isn't the New York Wheat Report. What about grape vines?

One of the first peer-reviewed studies of biodynamic compost on grapes appeared in the prestigious American Journal of Enology and Viticulture in 2005. Dr. Reeve and Dr. Carpenter-Boggs were co-authors on this study. A three-year study of application of BD compost vs. organic compost (the only difference being the addition of preparations 502-507).

Biodynamically treated vines in this study also received field sprays (preparations 500 and 501). I'll go more into the effects of field sprays in next week's post.

According to the paper: "No consistent significant differences were found between the biodynamically treated and untreated plots for any of the physical, chemical, or biological parameters tested....Also, no differences were found in the more sensitive measures of microbial efficiency known as biological quotients: dehydrogenase activity per unit CO2 respiration, dehydrogenase activity per unit readily mineralizable carbon, and respiration per unit microbial biomass."

Analysis of the grape chemistry showed very little difference among the three harvests. One exception was 2003, slightly increased (though statistically significant) Brix levels (25.88 vs. 25.55) and approximately 2.5% and 5% increases in total phenolic compounds and anthocyanins, respectively. From the paper: "Based on the fruit composition data, there is little evidence the biodynamic preparations contribute to grape quality. The differences observed were small and of doubtful practical significance."

OK, so maybe there isn't any practical significance in grape chemistry. The wine is what's important!

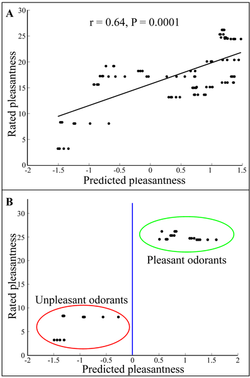

The same wine grapes from the 2005 AJEV study were vinified and compared in a trained sensory panel. The first test was to see if the panel could tell any differences between wines made from organic and biodynamic grapes.

From the paper: "Triangle test results indicated no significant differences at p<0.05 [that is, 95% probability that the result is not by chance] between the 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2004 biodynamically and organically grown Merlot wines."

Those that were able to correctly identify differences found slightly higher perception of in "musty/earthy" aromas in some of the organic wines. The only wine that was showed a notable preference was the 2003 vintage, where subjects preferred the organic wine over the biodynamic (p<0.1).

This is the same vintage where biodynamic wines had slightly increased Brix, and phenolics, which may explain the result that in that the 2003 biodynamic wine was notably (again, p<0.1) higher in bitterness.

This is hardly a resounding endorsement for the quality of biodynamic wine over wine produced organically.

If there really is an effect, then how might it work?

The possibility of an altered microbial population in BD compost found in the 2000 and 2010 studies led the authors to consider

microbial inoculation (i.e., the addition of beneficial microorganisms

from the preparations) as a possible reason for the change in the

compost. However, given the small inoculum (approximately 1 mg of

preparations per kg of compost), this mechanism was considered to be

unlikely but could not be ruled out.

I asked Dr. Carpenter-Boggs if

further studies have been done to examine the microbial makeup of the

compost. Her response was that the small, subtle changes in

biodynamic compost aren't really enough to justify further exploration

of the microbial makeup, which would likely be painstaking and expensive.

According to Dr. Reeve, "any mechanistic hypotheses are pure speculation at this point."

However, she seems to favor an explanation involving molecules that are capable of influencing plant and/or bacterial growth in small quantities. These hormones, molecules such as cytokinins, certainly exist in nature, but proving this hypothesis would be equipment and labor intensive, requiring extensive chemical analysis.

Dr. Reeve admits "it's quite possible that these results are flukes," and she argues that there aren't enough practictioners of biodynamics out there to gain a statistically significant grasp on the benefits of biodynamics over organic farming.

Conclusions

Compost as fertilizer performs better in many soil health metrics (micronutrients, microbial populations, etc.) than conventional mineral/NPK fertilizer. However, the differences between biodynamic compost and compost managed without biodynamic preparations are few and relatively subtle.

Compost with biodynamic preparations may have slightly altered microbial populations, but when BD compost is applied to crops, it gives little advantage over organic compost. Grapes produced using biodynamic viticulture treatments showed very little practical difference, and wine made from those grapes showed no statistically significant differences to a large panel of subjects.

Rigorous research into the effects of the biodynamic compost treatments may have produced small blips on the radar, but these results have either been inconsequential overall or irreproducible.

Further research may elucidate possible mechanisms, if any. Meanwhile, one consistent result is the beneficial effect of compost on crops. So while composting may be beneficial, there's little evidence to support the use of biodynamic compost preparations.

Further Reading

R Steiner, Agriculture, 1974 translation.

L Carpenter-Boggs et al., "Organic and biodynamic management: effects on soil biology." Soil Sci Am J., 2000

L Carpenter-Boggs et al., "Effects of biodynamic preparations on compost development." Biological Agriculture and Horticulture, 2000

JR Reeve et al., "Influence of biodynamic preparations on compost development and resultant compost extracts on wheat seedling growth", Bioresource Technology, 2010

JR Reeve et al., "Soil and Winegrape Quality in Biodynamically and

Organically Managed Vineyards", AJEV, 2005

CF Ross et al., "Difference Testing of Merlot Produced from Biodynamically and Organically Grown Wine Grapes." Journal of Wine Research, 2009.

Recent Comments