By Evan Dawson, Finger Lakes Correspondent

By Evan Dawson, Finger Lakes Correspondent

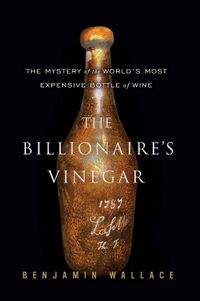

The Billionaire's Vinegar by Benjamin Wallace is, quite simply, the fastest and most enjoyable wine-themed book I've ever read. It is not, to use a rather nebulous term, the "best" book about wine I've read — that distinction rests with Neal Rosenthal's Reflections of a Wine Merchant — but it reads like fabulous and fabulist fiction, and that's a real credit to the author, considering it's not fiction at all.

The Billionaire's Vinegar tells the story of the most infamous bottle of wine ever sold, but it tells much more than that. In fact, I've spoken to several readers who found themselves let down initially that the story of the Thomas Jefferson bottle was wrapped up rather quickly. However, they all changed their minds after witnessing how Wallace employs the Jefferson bottle as a launch pad to take us deep into the world of the rarest and most avidly sought wine. Tasting a 1784 Yquem? You'll find not only the tasting notes, but the elaborate parties (some that lasted days) that were put together simply to affirm the majesty of such a bottle.

Wallace's sharpest skill is his tireless and proving research. He tells the stories of the wine world's most celebrated names — Robert Parker, Michael Broadbent, Jancis Robinson — drawn into the intoxicating chase for the rarest and most glamorous wines. The background, interviewing, and document digging alone must have consumed hundreds of hours for the author. Woven together, the story plays like The Da Vinci Code of wine, with one important exception: When you have finished reading you won't feel embarrassed to have been so captivted with the material.

Wallace's weakest moment as a writer comes when he strangely glosses over a hugely important point. The rare bottles were inscribed with the initials "Th. J.," but there were doubters out to prove that someone had faked the inscription — that Thomas Jefferson himself had nothing to do with the bottles. There is a connection to the Finger Lakes here, and I was surprised to see it covered so loosely. Without giving anything away, I can mention that Wallace writes, "Elroy had the bottles examined by two experts, one an engraver who worked near the Corning Museum of Glass in upstate New York." The subject gets a scant two paragraphs and is then dropped. Wallace should have identified the moment as the zenith of the investigation; the reader wonders from the beginning of the book whether those initials were legit or not. And as a bonus for New York state readers, the answer is revealed by local specialists!

Alas, not even the Corning Museum of Glass can provide more detail. A spokesperson told me that the expert cited in the book was not an employee of the museum: "The museum makes a point not to assess other people's objects," the spokesperson told me. "But we're happy to refer folks to other experts." Given that, I'm not sure why mentioning the museum was relevant to Wallace, but no doubt the folks in Corning are happy to have the free PR.

Hollywood is busy crafting a movie out of The Billionaire's Vinegar, but I'm not sure it will work. There is a delicious villain, but there is not a single "hero" worth cheering. Schadenfreude is not a lead character on the silver screen (though it plays gorgeously on the page).

In the end, ignoring the provenance of the wines, the reader has learned a great deal and enjoyed the lesson, thanks to sterling quotes uncoverd by Wallace — this one from the dean of California winemakers, Andre Tchelistcheff: "Tasting old wine is like making love to an old lady. It is possible. It can even be enjoyable… But it requires a leetle bit of imagination."