By Evan Dawson, Finger Lakes Editor with Tom Mansell, Science Editor

There is energy under our feet, and companies want to access it. The Marcellus Shale formation is about a mile deep, consisting of a rock-bound reservoir that runs through New York and Pennsylvania, among other states. According to experts, it's a natural gas basin that could provide 400 trillion gallons of natural gas.

There is energy under our feet, and companies want to access it. The Marcellus Shale formation is about a mile deep, consisting of a rock-bound reservoir that runs through New York and Pennsylvania, among other states. According to experts, it's a natural gas basin that could provide 400 trillion gallons of natural gas.

For sake of comparison, that's nearly 20 times the current national output.

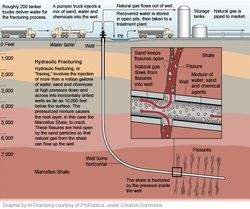

Crews can access the gas by drilling down — and then horizontally, hundreds of feet below the surface. The shale contains tiny pores where the gas is trapped and practically inaccessible by conventional means. A high-volume mixture of water, sand, and chemicals is pumped into the well, breaking up the rock and releasing the natural gas. The gas then is carried up the well line to the surface.

But it's the water mixture that makes people nervous. About 40 percent of that mixture returns to the surface and has to be treated. The rest remains below the surface, and opponents fear it will make its way up to the groundwater.

We've posted a graphic that illustrates the process (click it to enlarge). The graphic is from Al Granberg, courtesy of ProPublica under Creative Commons.

Finger Lakes Wine Industry Concerns

Opponents of hydrofracking in the Finger Lakes have two separate, very different concerns. The first centers on the surface wells, which some fear will create aesthetic pollution, harming tourism.

Sheldrake Point Vineyard Managing Partner Chuck Tauck recently sent a letter to his colleagues in the industry, warning of potential disaster. Tauck writes, "The impact on the tourism and the wine industry will be substantial, as our scenic rural and farm lands give way to industrial 200' drilling rigs, five-acre well pads and hazardous waste holding ponds spaced as closely as one for every forty acres!"

The final plans for surface well locations have not been released, but supporters of hydrofracking argue the wells are a small price to pay for significant gains for the economy and energy.

The second concern focuses on the potential for polluted groundwater. Companies use a mixture of water, sand, a blend of chemicals to free natural gas from the shale deep below the surface. The chemicals added act mostly to regulate the viscosity and consistency of the fluid.

These companies argue that the blend is proprietary, and thus they should not have to make the details public. But if there is contamination — to groundwater or to a worker involved in an accident — opponents say there's no way to know how to best handle it. A recent draft of the Supplemental Generic Environmental Impact Statement (SGEIS) contains a proposal requiring all new permitted wells to disclose the composition of their fracking fluid.

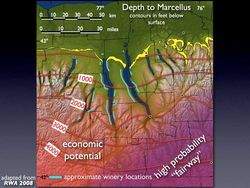

For the wine industry, this is about more than drinking water. It's no secret that large amounts of water are needed to produce wine, and polluted groundwater could harm entire vineyards. Opponents envision a ruptured well infecting groundwater and wiping out entire vintages. Environmental regulators contend that while mistakes are impossible to eliminate entirely, the safety record thus far has been extremely sound, with very low percentages of disruptions. The graphic below, adapted from Cornell Geology Professor Rick Allmendinger's website, shows the depth of the shale, its general economic potential, and the locations of wineries on the Finger Lakes.

"I understand the concerns - I do," an energy company executive, who asked not to be identified by name, told me. "But here's what happens: If one well has a problem, the media goes nuts with it. One family's well gets polluted water, and suddenly that becomes the only image that people attach to this process. And frankly that's not fair at all. We'd be out of business if this was a regular occurrence. It's in our best interest to do this as safely as possible, and when you compare this to just about anything else, it's extremely safe."

Opponents like Tauck contend that a relatively strong safety record could still include problems, and one is enough to do catastrophic damage. Tauck writes, "Unlike conventional drilling, drilling into the Marcellus Shale requires millions of gallons of water and chemicals, the disposal and regulation of which has been poorly addressed in the new document [the SGEIS], and has the potential to become a significant environmental disaster for the Finger Lakes, both with contamination of surface waters and contamination of aquifers and wells."

At present, hydrofracking is exempt from Clean Water Act regulation

since the fracturing occurs far below the level of groundwater.

The New York state DEC responds that regulators are comfortable that the hydrofracking process is safe and a very low risk to pollute groundwater. The fracturing happens hundreds of feet into the earth and the wells are created with thick liners. Energy companies point to a track record that includes a lower proportion of accidents than other energy exploration, including coal and oil.

Fewer Regulators to Handle Permits, Problems

Fewer Regulators to Handle Permits, Problems

New York state recently considered adding 30 workers to the DEC — a move that would have helped handle the long list of permit requests. More importantly, say skeptics, it would have provided a broader capacity to monitor problems with hydrofracking. But the state's budget crisis forced lawmakers to scrap those plans.

Pennsylvania recently added 40 environmental inspectors to help monitor hydrofracking, a move that has added at least some peace of mind for residents. Other states also feature stricter permitting. But as with other concerns, New York's DEC downplays concerns about handling this issue. A recent DEC email addressed the heavy interest in Marcellus Shale energy: "There have not been and will be no shortcuts in permitting — every well application will get all due scrutiny and oversight."

Even so, a study by the Cornell University Law School found that the DEC is currently not equipped to handle all the new regulations and oversight that the current draft of the SGEIS calls for.

Even those struggling to make up their minds on this issue seem to agree that more information would be helpful. But the DEC has taken the position that the expansion of hydrofracking plans is not moving too quickly, noting that one out of ten wells in New York state are already being hydrofracked and there have been no adverse environmental impacts. Winemakers across the Finger Lakes want to know what's in the chemical mixtures, what the immediate steps are to handle an emergency, and how long the surface wells will be around.

Galileo famously said that wine is sunlight, held together by water. In reality it's largely water, and it's vital that the water remain clean, hydrofracking or not.

Further reading: