By Tom Mansell, Science Editor

At TasteCamp, bloggers were generously treated to many library selections of riesling.

Peter Bell guided us through two vertical tastings of Fox Run Vineyards rieslings (one pictured at right), of the dry and semi-dry persuasion. Bob Madill poured a library flight at Sheldrake Point Vineyard, and the Tierce brothers poured three years of Fox Run, Anthony Road, and Red Newt rieslings (and their collaborative effort, Tierce Riesling). The oldest variations poured for the masses dated back to 2001.

One character in particular that stands out in many aged rieslings from around the world is the so-called "petrol" note. This aroma can be somewhat polarizing. It's "goût de petrol" if you like it and it's "kerosene" if you don't.

Many of the older Finger Lakes Rieslings we tasted along the way had a healthy dose of petrol, which is not surprising if you're at all familiar for riesling with a little age on it. What may seem surprising, though, is that a number of 2007 Rieslings we tried (and that I have tried in the past, even just after release) also had a bunch of petrol on them.

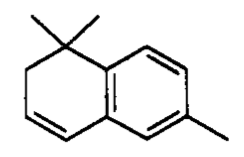

The aroma compound we're talking about is known as 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene, which is often thankfully shortened to TDN.

Where's this aroma coming from, and why is it appearing in newer rieslings?

Where's this aroma coming from, and why is it appearing in newer rieslings?

TDN itself is not often found in grape juice or in young wines. It originates from the gradual breakdown of protective plant molecules generally known as carotenoids.

Carotenoids are pigments that absorb light. They are important in leaves to support photosynthesis (and once the chlorophyll is gone from leaves in the fall, they give the leaves their oranges, yellows, and reds). In the berries themselves, these compounds absorb UV rays that would be harmful to the DNA and other cellular components.

Think of carotenoids as grape sunscreen. When UV light is high (i.e., in a year with lots of sunlight) carotenoids will build up during berry development to shield the cells from the harsh rays. Near the end of the growing season, the molecules break down into smaller components, some of which are precursors to very powerful aroma compounds, some of which are detectable in the parts-per-billion (micrograms/L) range.

These aroma compounds are often bound to sugar groups and known as glycosides when found in the must. Glycosides are not aroma-active, so they won't be observable by smelling or tasting the must per se. However, during fermentation, yeast enzymes liberate glycoside-bound aroma compounds, helping to create the complex bouquet that we love about wine.

So carotenoids can break down to form potent aroma compounds (1) during a hot harvest season or (2) by slow degradation of the compounds in the bottle over time. In a few years, a 2006 (from a cooler, wetter year) riesling may start to develop some TDN due to the bottle age, but some 2007s have already got some now due to the hot, sunny coditions. TDN formation can also correlate with water stress (and in some cases, atypical aging) but right now it's not clear whether the two are related or distinct phenomena. (aside: Yes, even in a relatively wet grapegrowing climate like the Finger Lakes, vines do occasionally suffer from water stress, which has led some growers to install drip irrigation systems.)

Not all carotenoid breakdown products are bad news, though. Beta-damascenone (cooked fruit, canned apple), Beta-ionone (raspberry, violet), and a fruity-smelling molecule known as riesling acetal are all carotenoid breakdown products, and are part of the essence of what makes wine "winey."

While it may seem like shading the grapes is a good way to reduce TDN (it is), there are many other reasons why it is desirable to have clusters exposed to sunlight and have an open canopy (see my post on leaf removal). A very recent paper in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, authored by a team of viticulture researchers at Cornell, addressed this issue.

Current evidence indicates that leaf removal immediately pre-veraison (33 days post-berry set) leads to increased TDN in the juice and finished wine. According to the authors,"growers could implement leaf removal at berry set or postveraison for disease control, etc., without a resulting increase in TDN. Conversely, preveraison leaf removal could be employed if higher TDN concentrations were desired in wine."

So, exposure sunlight can increase TDN precursors and hasten their conversion to sugar-bound TDN in the grapes, which is then released by fermentation. Alternatively, carotenoids can break down in the bottle, leading to increased petrol with age. This could explain why years like 2007, which was hot and dry, and great for red wine production, may not be the best years for Riesling, compared to years like 2006 and 2008.

I can't wait to see what the 2009 Rieslings have in store, but given the wackiness of that summer, I doubt there will be much petrol on them in their youth.