By Julia Burke, Niagara Correspondent

A while back I wrote about the difficulties of being a single wine taster in South Africa’s wine country, arguing that New York has a general edge when it comes to tasting room service for singles. In the interest of balance, I’d like to discuss something we can learn from the South Africans: the art of supporting local wine.

A while back I wrote about the difficulties of being a single wine taster in South Africa’s wine country, arguing that New York has a general edge when it comes to tasting room service for singles. In the interest of balance, I’d like to discuss something we can learn from the South Africans: the art of supporting local wine.

Here in New York, we look for restaurants that have one or two local wines on the list – and by “local,” we’ll settle for “within the state.” Winery employees hit the road relentlessly in an effort to get their wines into stores, attempting the often-difficult task of convincing shop owners that they can sell customers a New York red. Many folks want to support local, buy local, eat local – but when it comes to drinking local, there’s a disconnect between what is right and what is convenient.

“Locavore” is not a buzzword in South Africa’s Cape Winelands – it’s the status quo, and there’s no need for the offshoot term “locapour” because there is no other kind of wine drinker.

Folks that live in the Western Cape, especially within the areas that are designated Wine of Origin regions and districts (Stellenbosch, Paarl and Robertson, for example) don’t need to seek out local wine. Every supermarket and wine shop in town is packed with it. Forget about selecting restaurants based on their inclusion of local wines – finding a restaurant that serves at least one non-South-African wine is a challenge. And local food is a no-brainer: what goes better with South Africa’s dirty, lusty reds than gemsbock steaks or kudu loin from the game reserves of one of the world’s preeminent nations for hunting?

Once during my stay in South Africa I ate at a restaurant that was not within 30 kilometers of a wine region. My host, Blaauwklippen’s assistant winemaker, came prepared: he brought Stellenbosch wine from home in a wine cooler tote.

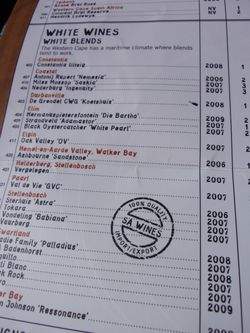

Balthazar Wine Bar on Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront takes local wine promotion to the next level. On a list (pictured right and at the top of this post) of some 300 wines, an entire page is devoted to explaining the wine regions of South Africa to the customer. I counted two non-South-African wines, a Mosel Riesling and a Loire red blend. The rest were grouped by style and described by region and sub-region, star rating in the beloved Platter’s Guide, food pairings (the menu features local seafood and game), and other awards. A friendly sommelier, well-versed in the nuances of each of South Africa’s many wine styles, makes selecting the perfect wine from this insane menu a little easier. Though Balthazar is in a class by itself in terms of sheer number of wines, this kind of attention to educating the consumer about the local wine scene was evident in nearly every restaurant I attended.

Balthazar Wine Bar on Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront takes local wine promotion to the next level. On a list (pictured right and at the top of this post) of some 300 wines, an entire page is devoted to explaining the wine regions of South Africa to the customer. I counted two non-South-African wines, a Mosel Riesling and a Loire red blend. The rest were grouped by style and described by region and sub-region, star rating in the beloved Platter’s Guide, food pairings (the menu features local seafood and game), and other awards. A friendly sommelier, well-versed in the nuances of each of South Africa’s many wine styles, makes selecting the perfect wine from this insane menu a little easier. Though Balthazar is in a class by itself in terms of sheer number of wines, this kind of attention to educating the consumer about the local wine scene was evident in nearly every restaurant I attended.

Why are South African wine drinkers such great supporters of local wine? First and perhaps most straightforwardly, local wine is more affordable for South Africans than anything from outside the country. South African producers are known worldwide for keeping their prices low and value high, and if outstanding local chenin blanc is available for $4 a bottle, why would a wallet-conscious South African go to the trouble of seeking out and ordering a $15 Vouvray?

But it’s not just a matter of dollars and cents. After all, there are producers in the famed Golden Triangle (from the Stellenbosch mountains to Helderberg) selling Cape Blends at $50-$60 a bottle. South Africans could get a cab/shiraz blend from Australia for $10 – but they don’t, which brings me to my second point: cultural pride. South African wine drinkers love their hometown wine regions. Wine farms are destinations, not just for tourists but for locals who want a family outing on a Sunday afternoon. They offer picnics, extensive playground equipment, romantic secluded tasting room areas for two – the idea is to spend hours or even the whole day relaxing with a bottle of wine. And the food at the wine farms, whether it’s a local cheese platter or a three-course dinner, is some of the most exceptional in the country. Live music, extensive tours, and other attractions make them some of the coolest places in town.

South Africans are proud of their country’s wine culture (one of the oldest in the world – vines were first planted by Dutch settlers in the Cape in 1652). They don’t want to be compared to Brand Australia and they don’t want to be more like France. It’s not isolationism, though the isolation of economic sanctions during apartheid certainly played a role in keeping South African wines within the country. It’s appreciation of living in a country with hundreds of wine farms making hundreds of different styles, competing, experimenting, making the best possible wines that they can. And if you’re thinking, “Pinotage isn’t all that great,” be aware that South Africans tend to make certain wines for export and keep the cream of the crop for themselves. Because of the level of competition and quality in the South African wine scene, wine enthusiasts can try everything from gamay to nebbiolo to pinot noir to tempranillo without venturing past the Wine of Origin sticker.

What can we New York wine and beer supporters learn from this? Last week I attended a round-table discussion between local wineries and retailers about how to sell more New York wine. Several concerns were raised: retailers felt their staff weren’t adequately educated to hand-sell a $25 New York wine; that consumers aren’t hip to the local wine scene and therefore don’t seek it out; and that without the support of restaurant wine lists, both shops and wineries are at a disadvantage.

The South African wine culture has some valuable lessons for us. First of all, restaurants that market themselves as havens of local, seasonal food need to be serving local wines. South African consumers are used to seeing their favorite local wines at restaurants, and we need that here. As consumers we can demand that our restaurants serve New York beer and wine – preferably from our neighborhood region but at least from within the state. (500 kilometers away is not necessarily “local” in South Africa – the idea is to introduce customers to wineries they can actually visit without a plane ticket.)

Wineries can also offer to help educate the staff at retail shops by hosting them at tasting and tour events. In South Africa, wine shop owners and restaurant owners are familiar with local wineries because they visit them and often know the winemakers. An educated staff translates into educated consumers, and there is enough quality in New York beer and wine to hook an educated consumer for life.

The price issue is, of course, a curve ball in the local wine problem here in New York, and one that deserves its own post, but I don’t think it’s insurmountable.

When customers visit Niagara tasting rooms and experience firsthand the excitement of a wine region in its infancy, when they get friendly, knowledgeable service and a little glimpse of where it all happens, they shell out $35 for a bottle of pinot noir more willingly than I ever would have thought possible. That’s the final lesson I think we can take from South Africa: if you’re a producer, make your winery a destination. Make it fun, make it an education for your customers and a memorable experience. The wine will do the rest.