By Donavan Hall, Long Island Beer Correspondent

Every few months or so our little brewery goes through a number of cylinders of compressed CO2 gas. It's an easy enough thing to load up the cylinders in the brewery truck and drive out to our compressed gas supplier in Riverhead — a one man job really, but it's more fun when there's two.

When Mike, my brewing and business partner, decided to turn our hobby into something a little more large scale and serious, he asked me if I wanted to be a part of it. So the two of us started Rocky Point Artisan Brewers (RPAB) three years ago. Since then we've added a third artisan brewer, Yuri. We're now the three musketeers of nanobrewing.

Right about the same time Mike and I started hatching RPAB I was madly trying to finish the first edition of my beer guide (it was during the 2009 Stony Brook Film Festival, I remember it well since I was proofreading my book during the intermissions between films, hoping that I'd meet the printer's deadline so I could sell the books at the annual craft beer fest held at Martha Clara in August), I started seeing Long Ireland Celtic Ale taps popping up in bars across Long Island. After a few inquiries I arranged a meeting with Dan Burke and Greg Martin of Long Ireland Beer Company. It turned out that I already knew Greg (by sight) from the B.E.E.R. Club (a local homebrew club) meetings.

In the last three years Long Ireland has grown to be one of the largest production breweries on Long Island with it's own brewing facility on Pulaski Street in Riverhead. And for the last six months I've been intending to head out for a peek at what Dan and Greg have built, so when Mike said, "Long Ireland's opening their tasting room for the first time today," it seemed like the perfect opportunity to pay Greg and Dan a visit at their new digs.

We picked up our gas cylinders and then Mike said, "You know where the brewery is right?" I said, "We'll find it, don't worry. I've got a nose for these things."

I thought perhaps there would be a sign. Just cruise up Pulaski Street and we're bound to see the sign. No sign, but when I saw the red and white building, I just felt in my bones that it was the new Long Ireland brewery.

"They need to paint the building green and yellow," I said. "To match the company logo."

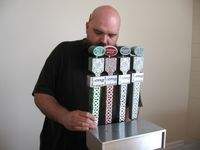

Mike parked the car in front of the brewery at 817 Pulaski Street, and I started snapping photos, eager to get back into my role of Long Island's craft beer documentarian. I could see Greg and Dan through the large plate glass windows of their new tasting room in the front of their brewery. Greg had a spray can of window cleaner and Dan was working on the bar, screwing on tap handles.

We were early, the tasting room didn't officially open for another forty minutes. "Don't let us distract you," Mike said. "Just put us to work." We're all in this together, after all.

So I helped pick up the place (to make it look neat) while Mike (the handy man) helped with the drain system below the taps.

When the tasting room was looking spiff, Dan said, "Hey, you guys wanna beer?"

When the tasting room was looking spiff, Dan said, "Hey, you guys wanna beer?"

Well, now that you mention it…

Mike started with the Breakfast Stout and I went with the Pale Ale. The Pale Ale was crispy, fresh, delightfully citrusy.

"This is your first time here, isn't is?" said Greg (pictured right).

It was. Greg opened the door leading to the brewery to show us the system that he and Dan had put together to brew beer.

The building that Greg and Dan are in is an wooden structure, like a big warehouse. There was something comfortable and homey about looking up and seeing the large wooden timbers holding up the roof. So many breweries are in these pre-fab metal buildings. Mike and I were envious of this space. Despite its size, the building had a charm, and a history.

Craft beer is more of a passion and an art than it is an industrial pursuit. Technically, breweries do manufacture a product, but we craftbrewers don't view it that way.

Craft beer is more of a passion and an art than it is an industrial pursuit. Technically, breweries do manufacture a product, but we craftbrewers don't view it that way.

Craft beer isn't just a mildly intoxicating beverage. It isn't just a product to be sold for money. Craft beer is food; it nourishes the body, and the soul. Craft breweries have to be small. Smallness is essential to maintaining the human contact with the food. Large-scale industrial manufacturing of food and all the packaging that goes with that system severs the connection between nature and humans.

This isn't just some mystical credo propped up by a neo-localist ideology — you can taste it. Food from a small farm, close to your home, tastes better than "industrial food." Anyone who's part of a CSA knows this, experiences viscerally, with the senses: not just the taste, but the look and the aroma. It's the same with the liquid food: beer. When humans make something with their hands, they imprint themselves on what they make — soul, humanity, beauty, connection. Machines can't impart what the body needs.

Greg (pictured right) and Dan's brewery might look big, but it's just about the right size to balance what is essential about the beer business. You have to be able to produce enough beer for sale that you can cover your expenses, but you don't want to produce so much that you lose the human connection. I've done the calculations. For two guys to make their living off brewing beer, they need about a 15 barrel brewing system.

Greg (pictured right) and Dan's brewery might look big, but it's just about the right size to balance what is essential about the beer business. You have to be able to produce enough beer for sale that you can cover your expenses, but you don't want to produce so much that you lose the human connection. I've done the calculations. For two guys to make their living off brewing beer, they need about a 15 barrel brewing system.

"We can boil twenty-two barrels at a time in our kettle," said Greg. "The system was built as a fifteen barrel system, but it's oversized. At twenty-two barrels we can brew three times a week and fill our fermenters."

Greg and Dan bought their brewing system third hand and installed it themselves. Their brewery is a product of conscientious human labor — it's a craft itself, a product of art and intelligence. When you build something yourself, you really know that thing.

The parts of the brewery were built twenty years ago — a custom order for New Haven Brewing, a brewpub. After three years of brewing, the brewpub decided to drop the "brew" part and just be a restaurant.

This happened to a lot of places in the early 90s, during the first wave of craft beer growth. At the time, more breweries opened than people were ready for. As a result, many brewers gave up or went out of business. Part of what hurt craft brewing back then was that non-brewers were getting into the business of making and selling a product. As a result, there was a lot of drinkable, but mediocre beer on the market. Many people's first experience of craft beer were at breweries that didn't represent the art very well, and people didn't taste the magic. A lot of very good breweries were brought down with those that were merely okay.

This happened to a lot of places in the early 90s, during the first wave of craft beer growth. At the time, more breweries opened than people were ready for. As a result, many brewers gave up or went out of business. Part of what hurt craft brewing back then was that non-brewers were getting into the business of making and selling a product. As a result, there was a lot of drinkable, but mediocre beer on the market. Many people's first experience of craft beer were at breweries that didn't represent the art very well, and people didn't taste the magic. A lot of very good breweries were brought down with those that were merely okay.

So, New Haven's system sat in storage for number of years until it was sold to Pennichuck Brewing in Milford, NH. In 2010 that brewery felt the pains of the economy and began shutting down its operations. Greg and Dan bought the brewing equipment from them.

When Greg and Dan got started a few years back, they had some help. The beer community is tight and we help our own. Competition doesn't really work as a business model if you really care about what you are making and not just the dollars that come out of the process. Rob Leonard of New England Brewing Company showed Greg and Dan the ropes — how to scale up from homebrew quantities to the volumes that would be needed to sustain a craft beer brewing business. The first batches of Long Ireland's Celtic Ale were brewed in Rob Leonard's Woodbridge, Connecticut brewery.

"When we told Rob where we got the brewing system, he couldn't believe it," said Greg. As it turns out, Rob Leonard was the brewer at New Haven Brewing Company back in the day, and the brewing system now housed in Long Ireland's building on Pulaski Street is the system that Rob brewed on twenty (some odd) years ago.

"Yeah, Rob's going to come down and make a batch with us, for old time's sake," said Greg. Small world.

I had just finished my Long Ireland Pale Ale as Greg told us that story. "That's a good story," I said. "And this is a fantastic beer."

Mike was done with his Breakfast Stout. "Yeah, I wanna try the Pale Ale next," said Mike.

"And I think it's Breakfast time for me," I said.

Greg led us back to the tasting room and poured us some tasters. Mike and I put our serious tasting faces on and sniffed the aroma. "What kind of hops are you using in the Pale Ale?" asked Mike. "I'm getting citrus. Cascade?"

"That's right," said Greg. "We used to use Amarillo, but that's getting hard to find for some reason, so we changed the recipe at bit. Now we're blending Columbus and Cascade."

I was enjoying the roasty, coffee-flavor of the Breakfast Stout. It had a slightly malty nose, and finished with a hint of sweetness.

It was time for the tasting room to officially open and the first customer was right on time. The guy put his growler on the bar. "Can I get that filled with the Pale Ale?"

Greg said, "Sure." And while he poured the beer he said, "Do you realize that you are our first customer ever? This is the first growler fill we've done here."

"Really?" asked the guy. "I thought you'd been open. I was just driving by with my growler."

Serendipity? Are there beer gods guiding the thirsty to craft beer oases?

It was about time for Mike and I to hit the road. As much as we'd love to stick around all afternoon and sample tasty beer, duty called. We had our own brewery that needed attention.

"Before we head out," I said, "can I get a sample of the Celtic Ale?"

Now, I'm very familiar with the Celtic Ale. That beer is everywhere. I've been having pints of it all over the Island for the last few years. Greg poured me a small glass. I tasted. It was definitely Celtic Ale, but there was something different. Something about it was fresher, more alive.

"Man, this is seriously good," I said impressed by the quality. "This is even better than it usually is."

"Thanks," said Greg. "I'm glad you like it."

But deep down, I knew why it tasted so good. Like spring water, there's nothing better than having craft beer at the source.

Note: Long Ireland's new tasting room will be open at 817 Pulaski Street in Riverhead each Thursday and Friday afternoon from 3 to 7. Saturday hours are 1 to 6. Growler fills are $11. If you don't have your own growler, you can buy one for $4 at the brewery. Two ounce tasters are free of charge.