To understand why the Hermann J. Wiemer 2010 Dry Riesling Reserve is such a special wine, it’s important to understand that not all rieslings are created equally. Nor are all wines created easily. Winemaking at Wiemer is more difficult, more patient, more risk, more reward. There is perhaps no better wine to exemplify this than the NYCR Finger Lakes Riesling of the Year.

To understand why the Hermann J. Wiemer 2010 Dry Riesling Reserve is such a special wine, it’s important to understand that not all rieslings are created equally. Nor are all wines created easily. Winemaking at Wiemer is more difficult, more patient, more risk, more reward. There is perhaps no better wine to exemplify this than the NYCR Finger Lakes Riesling of the Year.

“For me, the 2010 Reserve is the finest riesling I’ve made,” says winemaker Fred Merwarth. That’s an extraordinary statement for a winemaker who prefers euphemism to hyperbole, and who has built a prolific portfolio in 10 short years.

2010 was a long, warm growing season. It offered Finger Lakes wine producers options on when to pick. But stop there: picking at Wiemer doesn’t occur on one occasion, one weekend, one pass. Most wineries evaluate grapes and choose what they consider the ideal moment to pick. They’re looking for balanced grapes, good flavors, nice acidity, developed sugars. At Wiemer, each of the three vineyards is picked more than once during harvest.

The HJW Vineyard behind the winery was picked eight times in 2010.

“If you waited just on ripeness, you could end up with some problems in a year like 2010,” Merwarth tells me. “You could potentially get a riesling that’s soupy or higher in alcohol.”

To his point, many Finger Lakes winemakers have told me that they took the rare step of adding acid to their white wines in 2010. “I feel strongly about not adjusting acidity, because you don’t have to,” Merwarth says. “It’s already there.”

It is, if you’ve picked in multiple passes. The first pass at Wiemer happened on September 26, 2010; the last pass came on October 31. On each picking, Merwarth says he’s looking for different things. Early on, he’s looking for vibrant acidity that can provide the frame for a long-lived riesling. As the grapes continue to ripen and flavors develop, he begins to look for complexity and richness.

This approach paid off handsomely in 2010 when acids dropped more than usual in riesling vineyards that were unpicked into mid-October. While other wineries were left to decide whether to add acid out of the bag in the winery, Merwarth had several tanks that he could use from the early pickings, highlighting the crackling natural acidity that makes Finger Lakes riesling so noteworthy.

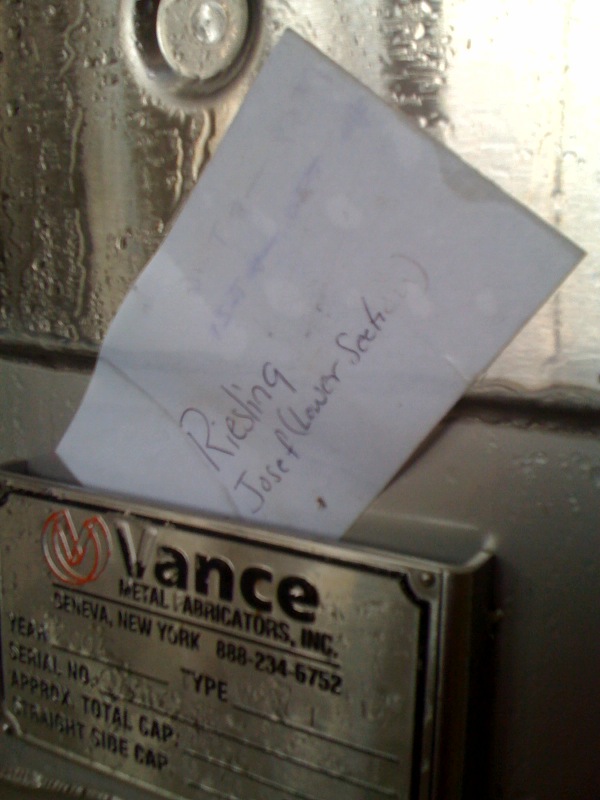

It was a vital tool, particularly because Merwarth took the Reserve bottling in an entirely new direction. He found himself drawn to the fruit from the Josef Vineyard in particular, which has never been a major component of the Reserve. In 2010, the Josef riesling was soft, round, extremely full and complex, but a bit lacking in natural acidity. Merwarth knew he could use the Josef riesling because those soft edges would be chiseled out by riesling from the earlier pickings up the road at HJW.

It was a vital tool, particularly because Merwarth took the Reserve bottling in an entirely new direction. He found himself drawn to the fruit from the Josef Vineyard in particular, which has never been a major component of the Reserve. In 2010, the Josef riesling was soft, round, extremely full and complex, but a bit lacking in natural acidity. Merwarth knew he could use the Josef riesling because those soft edges would be chiseled out by riesling from the earlier pickings up the road at HJW.

When the winemaker describes it, it sounds like an artist looking for the right colors on an oil canvas.

“We had this gorgeous fruit from Josef, and we thought we could make it half the blend for the Reserve,” he says. “But we knew it needed more. We had to decide how much from HJW, and how much from the Magdalena Vineyard. And from which pickings.”

Ultimately, Merwarth settled on a blend that included 35% of the stony-toned riesling from HJW. But it would take nearly a full year to come together.

In 2003, with Merwarth emerging into the winemaking role, Hermann J. Wiemer began using long fermentations (often known as cold fermentations). Many wineries crank up the heat on fermenting juice and control the temperature, coaxing a fast and easy fermentation. The juice can become wine in a matter of days, and be bottled not long thereafter. Merwarth wanted to know what would happen if the winery chose not to control the temperature and allow the juice to ferment “on its own,” as he likes to say.

The result is a process that can be finished by Christmas or still evolving into late-spring. But the 2010 rieslings tested Merwarth’s nerves with the slowest fermentations yet.

“August First,” he says with a laugh. “Unbelievable. They didn’t finish until August First. I thought they would never get there.”

But he knew very quickly that the wine would be special.

“It’s the texture,” Fred says, affirming the view of the NYCR panel that found the wine to be a standout in a blind tasting. “I always start with a goal of making clean wine. The second goal is complexity and balance. The third goal is more challenging, and we don’t always know why it happens. It’s texture. It’s a kind of weight without being heavy.”

That’s a spot-on description for the Riesling of the Year, and it’s a testament to Fred’s decision to hang the rich Josef fruit on a prickly HJW frame. The final wine is seamless, long, and almost certain to age beautifully.

“2010 was a very long growing season, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it was easy,” Merwarth points out. He’s right. The hard work and hard choices are reflected in a memorable riesling.