While I’m only nearing my two-year anniversary as a New Yorker, I feel a strong sense of local pride (perhaps it stems from my upbringing as a proud Texan). I support my local farmers markets, have helped out with harvest on Long Island, and have driven my fair share of miles on the Seneca Wine Trail. I have introduced my parents to New York riesling (proving two things: that riesling isn’t always sweet, and that New York makes good wine) and have a stash of age-worthy 2009 riesling hidden away for future enjoyment.

But what do non-American, non-local, non-inherently-prideful, somewhat-skeptical folks think about Finger Lakes wines?

I recently led a group of eight wine writers from Spain, France and Chile in an exploration of the Finger Lakes. Most of the journalists had never heard of the region previously. All write for traditional print publications, although some also write for blogs and other digital formats. All are seasoned tasters, many judge wine competitions, and all have worked in the industry for at least several years.

We piled into a 12-passenger van (I drove) and off we went, with Watkins Glenn as home base. We spent one day on Seneca Lake and another on Keuka Lake. We drank only Finger Lakes wines (and one local beer) during the visit.

The following is, by no means, an empirical analysis, neither in sample size nor in the comprehensiveness of our visit. However, I believe it is substantive enough of an experience to draw some interesting observations, and perhaps even conclusions.

We visited five wineries, and drank wines during lunch and dinner from another 12, totaling 17 wineries in all.

One French journalist observed the remarkable the quality gap between wineries, with the top ones being solid wines capable of international recognition, while others were still struggling, particularly in the red wines.

Others remarked at the price differential in wines. One winery, Red Newt Cellars, charged $48 for one of their top reds — a 2010 Glacier Ridge Cabernet Franc capable of aging very well (not unlike a Bourgueil, with herbal and green pepper notes in its youth), while another winery, Hunt Country Vineyards, offered all its wines for under $25 (with the exception of one library wine, a 2006 Vidal Blanc ice wine). The quality-to-value ratio was deemed more worthy at Hunt Country, even though the absolute quality of the first wine was better.

The sweet wine phenomenon, while discussed in depth prior to the visit, was still a shock — particularly when many, if not most, of the wineries cited the non-vinifera wines as their top sellers. Niagara and Concord varieties were deemed “sugared grape juice” or “like a candy.” However, there were a couple native and hybrid grape varieties that pleasantly surprised, including Hunt Country Cayuga White, with only a kiss of residual sugar at 2.5%, made in a drier style.

The grossly-generalized American proclivity for sweetness even carried over into vinifera wines. Several wines labeled “Dry Riesling,” like the 2011 Hermann Wiemer Dry Riesling, had a residual sugar of 0.9% and were deemed “not dry enough.” However, one of the demi-sec gewürztraminers, Eremita’s Semi-Dry Gewürztraminer (no vintage on label), was well-liked for the balance between acidity and sugars. It stood out particularly because it was bright and fruit-forward without an overbearing bitterness on the back palate described as “unattractive” to the European palate — something we found a lot of in the Finger Lakes gewürztraminers.

None of the journalists could palate any of the Finger Lake pinot noirs. Even Heart & Hands, ordered at dinner, was poured into the dump bucket by the glassful (locals cringed). I guess when Burgundy is the point of reference, it’s easy to see why the wines fall short. It’s important to note that none were familiar with Oregon pinot noirs.

I didn’t ask about knowledge of other New World pinots.

Two wineries rose to the top: Fox Run and Dr. Konstantin Frank. Interestingly, one of the journalists noted that, of the wineries we visited, these two had the cleanest winemaking and bottling operations. The assessment, I believe, was in actuality based on a number of other factors — obviously the quality of the wines, but also the well-situated and sophisticated tasting rooms, and perhaps the engagement of the owners in our tours and discussions. Favorites included the chardonnays and rieslings at Fox Run and the rieslings and rkatsiteli at Dr. Frank’s.

Of the wines that we tasted, but did not visit the winery, two wines were referenced as being “very good,” several times, by several people. Interestingly, they were from the same winery, enjoyed on two different nights. The first was a 2010 Lamoreaux Landing Wine Cellars Chardonnay. One visitor was actually reluctant to try it, stating that he was always disappointed in American chardonnay wines, his palate accustomed to white Burgundy. With a bit of prompting (coupled by the fact that I don’t think he liked riesling), he tried the chardonnay — and was pleasantly surprised. Oak was present, but it was subtle, old and well-integrated. Again, the acid backbone of wines from cool climate regions gave the wine a light-footed vibrancy that I believe many American chardonnays often lack.

Of the wines that we tasted, but did not visit the winery, two wines were referenced as being “very good,” several times, by several people. Interestingly, they were from the same winery, enjoyed on two different nights. The first was a 2010 Lamoreaux Landing Wine Cellars Chardonnay. One visitor was actually reluctant to try it, stating that he was always disappointed in American chardonnay wines, his palate accustomed to white Burgundy. With a bit of prompting (coupled by the fact that I don’t think he liked riesling), he tried the chardonnay — and was pleasantly surprised. Oak was present, but it was subtle, old and well-integrated. Again, the acid backbone of wines from cool climate regions gave the wine a light-footed vibrancy that I believe many American chardonnays often lack.

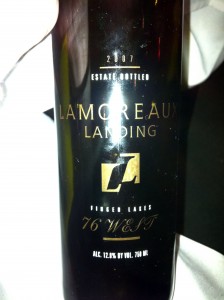

The second was the 2007 Lamoreaux Landing 76 West, an estate-bottled Meritage-style blend. This wine was ripe but not jammy, herbal but not green, assertive without being overbearing, and most impressive to me, could stand alone but played very well with ribeye (dinner Saturday night). It was by far the most sophisticated of the reds that we tried, at a very pleasant 12.8% alcohol.

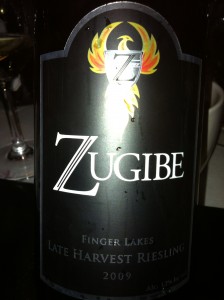

Another unexpected surprise: 2009 Zugibe Late Harvest Riesling. Our server told us an interesting story about the wine: It was an unplanned but fortituously vinified wine. The fruit hung on a winegrower’s vines with no home. Zugibe was offered the grapes, decided to give them a try, and ended up making an award-winning late harvest Riesling. It’s an untraditional after-dinner choice (the viscosity of the wine is unlike a desert wine, but it is sufficiently sweet and apricot-y) and is a steal at $36 for a 750mL on Red Newt Bistro’s restaurant wine list.

Another unexpected surprise: 2009 Zugibe Late Harvest Riesling. Our server told us an interesting story about the wine: It was an unplanned but fortituously vinified wine. The fruit hung on a winegrower’s vines with no home. Zugibe was offered the grapes, decided to give them a try, and ended up making an award-winning late harvest Riesling. It’s an untraditional after-dinner choice (the viscosity of the wine is unlike a desert wine, but it is sufficiently sweet and apricot-y) and is a steal at $36 for a 750mL on Red Newt Bistro’s restaurant wine list.

For the European visitors, the American market is of utmost interest — clearly a lot of wine is getting consumed here, much of it from Europe. EU wine consumption fell by almost one million hectolitres in 2011, while consumption rose in the United States by 0.9 million hectolitres in 2011 compared with 2010 to reach 28.5 million hectoliters, according to the Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV). Thus, exports are becoming increasingly important to the European wine industry.

Other interesting tidbits:

Our distribution system is so complex and varied from state-to-state that the international visitors had many, many questions. They were very interested in the grocery store versus wine shop dynamic in New York State.

The lakes impressed with their beauty and fall foliage; one French journalist declared that he would retire to the region to make wine.

There’s a deep interest in viticulture, microclimates, terroir and winemaking techniques.

There was a bit of surprise – perhaps even shock – that chapetalization (the adding of sugar) is allowed – many regions in Europe forbid it.

But the key takeaway, through the eyes of an international visitor and my own, is the remarkable youth of the region, and how much opportunity there is for wineries and winemakers to work together to advance the quality of the region. With that comes the international prestige that the Finger Lakes so ardently seeks.