About 5,000 people live in Walton, New York, an unassuming town on the edge of the Catskills whose main drag is lined with quaint brick buildings and come fall, so many scarecrows that it’s sometimes called ‘Scarecrow Capital of the World.’

Walton might also earn a prominent spot in the story New York’s modern cider boom as the home of Awestruck Ciders. I took the hilly, two-and-a-half hour drive to Walton recently after sampling some fizzy Eastern Dry, a vaguely tropical cider that was so poised — and at $9 for a 750-milliliter bottle, so well-priced — that I thought the people who made it might be both very talented and very smart.

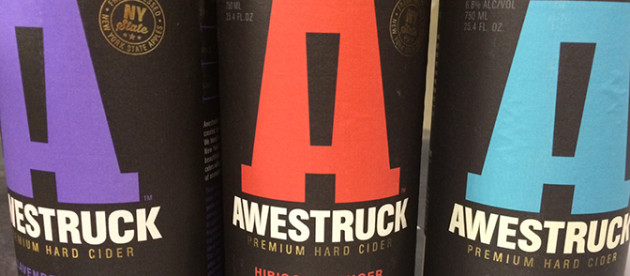

Turns out, they’re also super-friendly and full of stories. Twentysomethings Patricia Wilcox and Casey Vitti crisscrossed the globe for years before returning to their hometown to create a trio of ciders — Eastern Dry, Hibiscus Ginger, and Lavender Hops — that though only two years old are already sold in 32 New York counties. In fact, Vitti and Wilcox are scrambling to keep up with demand. It’s a familiar story in the hard-cider boom — but it didn’t come after an epiphany. Instead, Vitti and Wilcox came to cider making gradually. “It was lots of little steps that came together,” said Wilcox as we sit on stacked milk crates around a steel table in the middle of their space, a windowless former meat processing facility with concrete floors.

Turns out, they’re also super-friendly and full of stories. Twentysomethings Patricia Wilcox and Casey Vitti crisscrossed the globe for years before returning to their hometown to create a trio of ciders — Eastern Dry, Hibiscus Ginger, and Lavender Hops — that though only two years old are already sold in 32 New York counties. In fact, Vitti and Wilcox are scrambling to keep up with demand. It’s a familiar story in the hard-cider boom — but it didn’t come after an epiphany. Instead, Vitti and Wilcox came to cider making gradually. “It was lots of little steps that came together,” said Wilcox as we sit on stacked milk crates around a steel table in the middle of their space, a windowless former meat processing facility with concrete floors.

Long before they were a couple, the two attended high school together in Walton before striking out into the world separately: she to college and he to the U.S. Air Force Academy; Wilcox to study abroad in Bolivia, Vitti to France to work as an electrician in a chateau. “Eventually, we both ended up back in Walton, reconnected, and then spent the next few years working and traveling to as many places as possible,” said Wilcox.

During their travels, Vitti and Wilcox frequently sought out off-the-beaten-path beverages such as “interesting beers,” egg creams, Thai iced tea — and hard cider. “We discovered cider before it hit the U.S.,” said Wilcox, in places such as Argentina, France, and Spain. In summer 2013, Vitti and Wilcox returned back to Walton after managing a hotel in Costa Rica. “We said, we’re home, we’re bored, what are we going to do?”

Wilcox’s father had once grown apples and made sweet cider, and they knew that apples grew prolifically upstate New York. Vitti had also experimented with fermentation. “We thought, how cool would it be to make cider?” said Wilcox.

On July 1, 2013, the pair founded Gravity Ciders, whose name riffed “on the idea of science and cider and nature,” said Vitti, and also evoked that famous apple that pelted Isaac Newton in the head. They applied for their alcohol permits almost immediately, and while they waited out the process, set about sourcing apples — and quickly discovered that cider apples, which are more tannic and bitter than the apples we eat, are nearly impossible to find, at least enough to supply a fledgling cider business. “On a commercial level, it’s expensive and difficult to get true cider apples,” said Vitti.

They eventually came across some they liked from George W. Saulpaugh & Son in Germantown. “We found the place when we were researching Lady Apples, which add unique flavor that helps balance out acid levels,” said Wilcox. “I think it’s technically a cooking apple, but it has a lot similar traits to cider apples.”

Soon, they turned out five-gallon test batches using “a rigged-up press” cobbled together, in part, from a stainless-steel garbage disposal. “[Lady Apples] taste like dried fruit, and when you grind them, they smell like Cheez Doodles,” said Vitti. The initial system was so delicate that they had to quarter the apples before pressing.

Soon, they turned out five-gallon test batches using “a rigged-up press” cobbled together, in part, from a stainless-steel garbage disposal. “[Lady Apples] taste like dried fruit, and when you grind them, they smell like Cheez Doodles,” said Vitti. The initial system was so delicate that they had to quarter the apples before pressing.

In a way, practicality determined style: The two thought that sourcing apples might grow more difficult as the cider sector grew, and so they decided to produce flavored ciders — even though Wilcox loves deeply colored, funky, “horse blankety” ciders. Since their original name, Gravity Ciders, was already in use by another company, they chose Awestruck Ciders for the bottles themselves — which they thought spoke to the range of expression that cider can achieve. “One can be bone-dry, one will taste like candied apples. It’s amazing what [cider] can do,” said Vitti. To help drinkers navigate their trio of styles, they took a cue from Bully Hill wines and printed a slider on each bottle label that indicates sweetness and acidity.

By summer 2014, Gravity/Awestruck Ciders’ permits were in place, and Vitti and Wilcox began commercial production of Eastern Dry and Hibiscus Ginger. Rather than deliver their ciders themselves, they signed on with distributors from the get-go; demand grew so quickly that pressing their 3,200 pounds of apples into 250 gallon batches on an outdated system was almost ridiculously slow. “It was taking us two days to do what others could do in a few hours,” said Vitti. Instead, they decided to purchase already-pressed apples and flavor and ferment them in their own facility — fermenting them for two to three weeks before blending them in a former beer ‘brite’ tank for blending and carbonation.

The results are poised. As we talk, Wilcox pours out salmon-hued samples of Hibiscus Ginger. Though technically, the sweetest in their line, Awestruck’s ’entry’ cider also has a bristling acidity that keeps its elements in balance. “We love dry ciders, but we wanted this to be a gateway,” said Vitti. “People think hard cider is supposed to be like sweet cider. We wanted people to say, we like Hibiscus Ginger. What’s next? They might start with this and move on to Eastern Dry.” They might also try Lavender Hops, an off-dry, floral cider with a pinelike backbone.

The results are poised. As we talk, Wilcox pours out salmon-hued samples of Hibiscus Ginger. Though technically, the sweetest in their line, Awestruck’s ’entry’ cider also has a bristling acidity that keeps its elements in balance. “We love dry ciders, but we wanted this to be a gateway,” said Vitti. “People think hard cider is supposed to be like sweet cider. We wanted people to say, we like Hibiscus Ginger. What’s next? They might start with this and move on to Eastern Dry.” They might also try Lavender Hops, an off-dry, floral cider with a pinelike backbone.

Vitti and Wilcox now have a rolling production of 500 gallons a week, and growth has come so rapidly that the couple are looking for a bigger space, maybe even with a tasting room. They’ve also begun selling kegs of cider to the bar trade, planted an 80-tree “hobby orchard,” and hired a production assistant to take the edge off 70-hour work weeks, And they’re playing with a few new flavors, including a cloudy scrumpy that tastes like a blend between sour Belgian beer, citrus, and pressed apples, and could become their fall seasonal.

Wilcox thinks the fact that Awestruck and other craft ciders are being sold in supermarkets (I found mine at DeCico’s in Brewster) heralds change with regards to popular tastes. “It’s an exciting time for crafted beverages,” she said, as going to the supermarket to buy some beer or cider is no longer a rote task — instead, it’s a way to create an experience. “It was important to us to make something that was a whole experience. And it [cider making] suits us in more ways than we ever imagined.”