Editor’s Note: Every Thursday — call it Throwback Thursday if you’d like — we’ll pull a story from the more than a decade of NYCR stories and republish it. This week, I pulled a story that managing editor Evan Dawson and science editor Tom Mansell teamed up for about synthetic closures in the Finger Lakes.

Serious wine consumers are not, generally speaking, fans of synthetic cork. Most recoil at the sight of a plastic cork being pulled from a bottle they had otherwise been excited to open. Is this bias unfair? Maybe. Companies are working to improve the quality of synthetic corks. We’ll get to that in a bit. But there’s no denying that synthetic corks make a clear statement to the serious consumer, whether intended or not.

“Cheap,” said one of the many tasters on the evening of the recent Finger Lakes Riesling Hour. The inaugural riesling launch event led to coordinated tastings around the state and beyond. In Rochester, we had a packed room and it wasn’t long before someone noticed that several 2010 Finger Lakes rieslings were closed with synthetic corks. In particular, the synthetic closures on Dr. Konstantin Frank and Rooster Hill stood out at our tasting. We’re told that a few other Finger Lakes rieslings opened that night were also closed with synthetic.

“I hate them,” says Leo Frokic, a downstate wine aficionado. “They let oxygen in. Would never buy anything worth aging that was sealed with synthetic corks.”

“If I see plastic, I worry,” says Loren Sonkin, owner of Sonkin Cellars, which makes California syrah blends. “I won’t buy wine to age if I know it is in plastic. I am disappointed in the winery and left wondering why.”

Synthetic closures are mostly made from petroleum-derived polymeric materials. Essentially, they are plastic. And the types of plastic that synthetics are made of are not good oxygen barriers. While wine aging is a complex chemical phenomenon, it’s generally agreed that oxygen plays an important role in the evolution of a wine in the bottle. Studies consistently show that synthetic closures have a higher oxygen transfer rate (OTR) than cork or screwcap closures. In general, cork, being a natural product, shows the most variation in OTR, while screwcaps are consistently the lowest and synthetics are consistently higher than cork.

So let’s attempt to answer Sonkin’s question: Why are some of the top Finger Lakes wineries using synthetic corks to close their rieslings? We posed that question to Fred Frank, owner of Dr. Konstantin Frank Vinifera Wine Cellars on Keuka Lake.

Cost

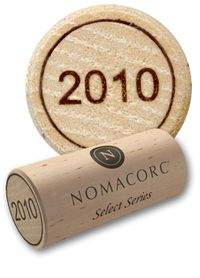

Frank explained that the price of each individual Dr. Frank bottling determines their use of closure. Their most expensive wines are closed with high-grade natural corks. “In our mid-priced wines, we use synthetic corks from Syncor,” Frank explained. “These corks are imported from Germany and the manufacturer claims they perform the best in testing run by a university. In our lower-priced wines, we use synthetic corks from Nomacorc.”

Frank’s decision to base the closure on the wine’s price leads to a potential problem. Dr. Frank’s 2008 Meritage, for example, sells for twice the price of the 2010 Semi-Dry Riesling. But history suggests that the riesling will outlast the Meritage in your cellar.

Synthetic corks offer a significant potential savings, but there are levels of quality with each kind of cork. Natural corks run from about $0.20 apiece up to roughly a dollar. Most wineries tell us that they use natural corks that cost either $0.26 apiece or just about twice that. Synthetic corks can come in around a dime apiece, but the price can rise to the natural cork level for the new, higher-end versions. A winery that produces 10,000 cases of wine annually could save $36,000 by switching from higher-end natural cork to lower-end synthetic cork. Would the wine suffer? Over the long term, almost certainly yes. But again, winery owners know that most consumers don’t have a long term.

Closure contamination

Last year, Rooster Hill owner Amy Hoffman explained why she chooses synthetic cork instead of natural cork for Rooster Hill’s rieslings.

“(Winemaker) Barry Tortolone and I have discussed this at length,” Hoffman said. “The biggest reason is to ensure corked wines are not poured in restaurants that typically don’t have good trained staff that may recognize tainted wine. The last thing I want is for some family to drink a bottle of wine that is not right and then judge our wines by that experience.”

Winery owners have stressed how frustrating it is for them to discover that even a small percentage of their wines are corked, ruined by TCA that shows up in the wine in the form of various off aromas. They also worry that some wines might contain sub-detection threshold levels of TCA, which can mask fruit aromas without being perceived as tainted, so it’s difficult for the customer to discern whether the problem is with the cork or with the wine itself. But isn’t the problem getting better? Haven’t corks improved, making cork taint less likely?

Estimates on TCA contamination vary, depending on whom you ask. The cork industry claims that cork taint incidence numbers continue to decrease, and estimate that less than one percent of bottles are “corked”. Critics, meanwhile, claim numbers of anywhere from five to ten percent. In more objective measures, data collected from the International Wine Challenge, where judges are trained to sniff out faults, shows that cork taint shows up in just under two percent of bottles (2006-2008 data).

“Premium factor”

Another point often raised in the Finger Lakes is the fact that the vast majority of consumers are not, in fact, laying bottles down to drink months or years down the line. Most wines are purchased for quick, almost immediate consumption. Why should a winery pay more for natural corks when a synthetic cork will do the job for at least a short while?

From our perspective, here’s a strong reason to use the best possible closure: You won’t effect change if you’re signaling to the consumer that the wine should be drunk quickly, just as it always has. Finger Lakes wineries are producing some truly fine rieslings, and year after year, we find new evidence that the wines will age with grace and beauty. Some have even showed the capacity to improve over a decade or more. But consumers are not likely to begin laying bottles down if the message they receive is that it’s not worth their while to do so. Change comes slowly, and with persistent consumer education. It’s not always the cheapest short-term option that leads to long-term success.

This consumer perception of quality based on bottle closure is gleefully referred to by the cork industry as “premium factor.” To many consumers, there is just something special about popping a natural cork out of a bottle. One study of this phenomenon seems to confirm its existence, with consumers showing a strong positive association (e.g., they would pay more) for wines sealed with natural cork. Screwcaps show a strong negative correlation (perhaps a holdover from the Carlo Rossi jug wine days) and synthetics also show a mild negative correlation. Savvier consumers know, though, that screwcaps are not just for plonk, as many high-quality New World wines on screwcap demonstrate. But you don’t see entire countries (à la New Zealand) switching almost all of their production to synthetic closures.

In the minds of consumers, natural cork is simply the best possible closure for aging a wine. While the jury is still out on the scientific basis for such a belief, the court of public opinion has long been adjourned.

At a recent writers conference, Evan had the chance to see the new lineup from Nomacorc, a synthetic cork producer popular with New York wineries. The lower-end synthetics still look as fake as ever, and their oxygen transfer rates would be trouble for a consumer looking to lay bottles down. Their higher-end products look much more like natural corks than ever before. It’s a clean, strong look. How do they perform? For the Nomacorc Select Series, their top-of-the-line product, the OTR is comparable to mid-range natural cork, providing, according to Nomacorc, a shelf life of between six and eight years.

At the conference, Evan tasted a series of wines that were several years old, closed under different grades of Nomacorc. On each occasion, he was able to correctly identify which wine was closed under better quality synthetic cork, and which was closed under lower-quality synthetic cork. But it wasn’t easy.

There are numerous factors that producers need to consider when choosing bottle closures for their wines. Longevity, consumer perception, cost, risk of taint from the closure, and many more. There are also alternatives for wineries who wish to eliminate cork taint. Screwcaps are an option of course, but bottling under screwcap (1) requires a new bottling line (a capital cost many wineries simply can’t justify), and (2) comes with its own share of problems, which are beyond the scope of this piece. Some technical (agglomerated) corks (e.g., DIAM) undergo a special treatment process to remove TCA, but this process also adds to the cost. Then there are a host of other alternative man-made closures like the Zork, the VinoSeal, the Guala Seal, and many others, whose market acceptance and performance as closures are yet to be determined.

It’s easy for us to prod Finger Lakes producers about natural corks when we’re not paying the bills. And if we were producing Cayuga White or Niagara or many other varieties, we’d not spend extra cash on natural cork. That said, this is a region looking for more worldwide respect. This is a region that produces many wines that merit such respect. Most of the top producers close their rieslings with natural cork, but not all. It’d be a shame to see writers and consumers open a bottle and give up on the wine — or the winery, or even the entire region — before they pour a glass.