By Evan Dawson, Managing Editor

In Niagara, winemakers use the word "terroir" often. We heard it just about everywhere we went. It's a word spoken far less often in New York state, where winemakers speak of sense of place or perhaps "somewhereness," while occasionally dropping "terroir" into conversation as well.

Why does this matter? It's not simply relevant because Canadians speak a lot of French. It's relevant because in Niagara, where I spent several days for TasteCamp North, "terroir" is not about marketing. It's about an honest exploration of the soil and what it can provide.

This is no small detail. In Niagara, there is money. I mean, serious, serious cash. Some of the estates (Chateau des Charmes, Hillebrand, Tawse) look like they were pulled out of Napa, polished new, and dropped in Canada. And it's comforting to know that all of that money (often coming from the Toronto business community) isn't just purchasing attractive buildings and new barrels (though there are piles of new barrels — a little too many for my taste). The owners of these estates have very obviously invested in high-quality winemakers and well educated vineyard staffs.

And that means that Niagara is populated with soil geeks.

I found similarities between the best wines of New York state and the best wines of Niagara, Canada. But more interestingly, I found that the soils and climates of New York state, which show great variation from the top of the state down to Long Island, are mirrored in a much tighter Canadian space. For tourists, that sets up some fascinating possibilities.

First stop: Niagara-on-the-Lake

Like Long Island, Niagara-on-the-Lake is showing some success with Bordeaux varieties. And like Long Island, the best Bordeaux variety wines are outstanding in any setting, and compared to wines from any region.

Niagara-on-the-Lake can pull this off thanks to a warmer climate than the rest of the region. It's farther away from the lake, which means an earlier spring and a longer growing season. In years like 2007 and 2010, red grapes can enjoy all the ripening they want, and then some.

At the stunningly beautiful Chateau des Charmes (part of their vineyard pictured right), we enjoyed an informative chat with proprietor Paul Bosc, Jr. Paul couldn't help but point out that despite any presumptions we might have about Canadian wine regions, his vines didn't lag Bordeaux by all that much and actually benefit from more ripening in the peak of summer than most French vines. Paul took the Bordeaux comparison indoors during lunch, where we had the opportunity to see how high the quality could go.

At the stunningly beautiful Chateau des Charmes (part of their vineyard pictured right), we enjoyed an informative chat with proprietor Paul Bosc, Jr. Paul couldn't help but point out that despite any presumptions we might have about Canadian wine regions, his vines didn't lag Bordeaux by all that much and actually benefit from more ripening in the peak of summer than most French vines. Paul took the Bordeaux comparison indoors during lunch, where we had the opportunity to see how high the quality could go.

We were presented three barrel samples from the prodigious 2010 vintage. All were bound for the Equuieus bottling, a top-flight cuvee that is only produced in strong vintages. The three samples showed varying levels of new oak. The sample with neutral oak was easily the most complex, allowing pure fruit to show muscle and grace. I figured it to be an easy winner, the main component for a coming blend that could be dazzling.

Then Paul took a show of hands. Fewer than 20 percent favored the this sample. And if writers prefer the sweet, oaky flavors in the other samples, is there any doubt that customers would, too?

Paul spoke about the assumptions and bias that his region must face. He is clearly proud of the Equuieus bottlings, and understandably so. But these wines are, to me, impeded by the oak and lack the elegance present in great wines. And here was a touch of irony: Paul speaks about terroir, but he masks some of the nuance of his soil with that expensive wood.

Here's the good news: Chateau des Charmes is setting the pace for big Canadian wines, and Paul's staff has the luxury of winemaking options. My guess is that eventually they'll dial down the heavy oak and put their impressively structured wines out front. But anyone who doubts that red wine can thrive in Canada should stop at this estate.

Now, in New York state, the transition from a region that succeeds with Bordeaux varieties to a region that champions cooler climate varieties is only about a five-hour drive. From the North Fork to the Finger Lakes, the New York wine landscape changes with the soils, the slopes, and the slightly cooler climate. Niagara-on-the-Lake is very much flat, evoking Long Island. But in Canada, you don't need five hours to reach the next wine region. It's a half-hour's drive west, to the Beamsville Bench. The terrain begins to rise and fall, and out here, closer to the lake, the spring starts more sluggishly. But when it does, it's riesling and pinot country.

Next stop: Beamsville Bench

We had tasted a few rieslings from Niagara-on-the-Lake that I'd like to forget about, and thankfully the wines of Beamsville Bench helped me do just that. I was simply enthralled with the rieslings from 30 Bench Winery, a smaller producer that focuses heavily on riesling and cabernet franc.

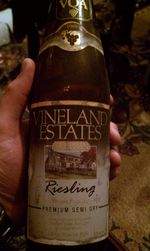

We visited a larger producer that also focuses strongly on riesling and cabernet franc, with results no less captivating. Vineland Estates is another fairytale setting. We arrived to find a wedding on the property.

But it's not all cartoons and fireworks here. Winemaker Brian Schmidt (pictured right addressing our group) could talk about his vineyards all day long, and he's so compelling that you might find yourself listening for as long as he wants to pontificate.

But it's not all cartoons and fireworks here. Winemaker Brian Schmidt (pictured right addressing our group) could talk about his vineyards all day long, and he's so compelling that you might find yourself listening for as long as he wants to pontificate.

Interestingly, Brian says that he and the vineyard staff tried to cut down on the cropload several years ago. "We heard so much talk about low yields and higher quality, so we wanted to see what would happen if we made some changes," he explained. "But take an experienced vineyard, and you'll find that it knows what it wants. IT knows what it needs. We thought we had dropped fruit and made the changes to achieve around two tons to the acre, and wouldn't you know it? It produced almost exactly the same tonnage that it was producing the previous year."

So instead of trying to manipulate his vines and soil, Schmidt says he lets it decide what it wants to produce. The wines indicate it's the right approach.

So instead of trying to manipulate his vines and soil, Schmidt says he lets it decide what it wants to produce. The wines indicate it's the right approach.

This is one of the rare producers that not only lays down a large amount of wine; it allows customers to taste and purchase library wines in the tasting room, every day. We saw wines from the early-to-late 1990s available for only $25 per bottle. That's practically stealing, and it's stealing a piece of history.

Now, it's only interesting if the wines have longevity. At Vineland Estates, the rieslings certainly do. I found a 1998 riesling to be tired, but a 1989 riesling — opened by Brian in a spur-of-the-moment, what-the-hell-why-not decision — was a marvel.

The 2010 lineup, still developing, promises to be special. A richer, balanced bottling will be set aside for five years before the public can taste it. For me, it was the wine of the weekend. And the Vineland Estates 2002 Cabernet Franc was stunningly fresh and vibrant, and saw no oak at all. Brian explained it went through micro-ox, and I was surprised to find it had plenty of verve and complexity.

The soil exploration was at its most intense at Tawse Winery, a biodynamic estate that produces perhaps the best pinot noir in Niagara.

For all of the heated debate about biodynamics, winemaker Paul Pender (right) brings an utterly refreshing lack of militancy to the discussion. He happily showed off the winery's dynamizer, and spoke of burying cow horns filled with excrement, but it's clear that for Pender, biodynamics is not about religion. It's about a practical approach to cultivating the healthiest vineyards and producing the best possible wines.

While the Tawse pinots are excellent, the chardonnays were attention-getting. Pender's unoaked chardonnay is a precise, crackling version of this grape that is so often punished with wood. In fact, the only misstep in the Tawse portfolio is the Meritage blend, but then, this isn't Niagara-on-the-Lake.

The conversation about soils continued all weekend long. Wine lovers might be surprised at the sophistication on display in this region. With more than 100 wineries, tourists can enjoy a glitzy, glamour wine tour, or they can make appointments and get down in the dirt with some world-class winemakers. Unlike many emerging regions, Niagara is not banking on a single variety. There's too much diversity in soil, landscape and climate. It's like having the Finger Lakes wedged up against Long Island — why narrow the search when a broad exploration makes sense?

A word about Niagara Chardonnay

The region is clearly excited about its chardonnay. I favor a Chablis-like profile in chardonnay, unoaked and edgy. We didn't taste much unoaked chardonnay during TasteCamp, but I'm told many wineries make both an oaked and unoaked version. My advice: Ask for the unoaked.