Conveying a sense of place has become a real priority for fine wine, no matter where in the world it is grown. Wine has the responsibility of not only needing to taste and smell good, but for afficianados and for marketing purposes it is expected to also serve as a reliable ambassador for its region of origin. It’s supposed to mean something when you see a unique place name on a bottle’s label, and before long it just might mean that it is coming from New York’s North Country.

Conveying a sense of place has become a real priority for fine wine, no matter where in the world it is grown. Wine has the responsibility of not only needing to taste and smell good, but for afficianados and for marketing purposes it is expected to also serve as a reliable ambassador for its region of origin. It’s supposed to mean something when you see a unique place name on a bottle’s label, and before long it just might mean that it is coming from New York’s North Country.

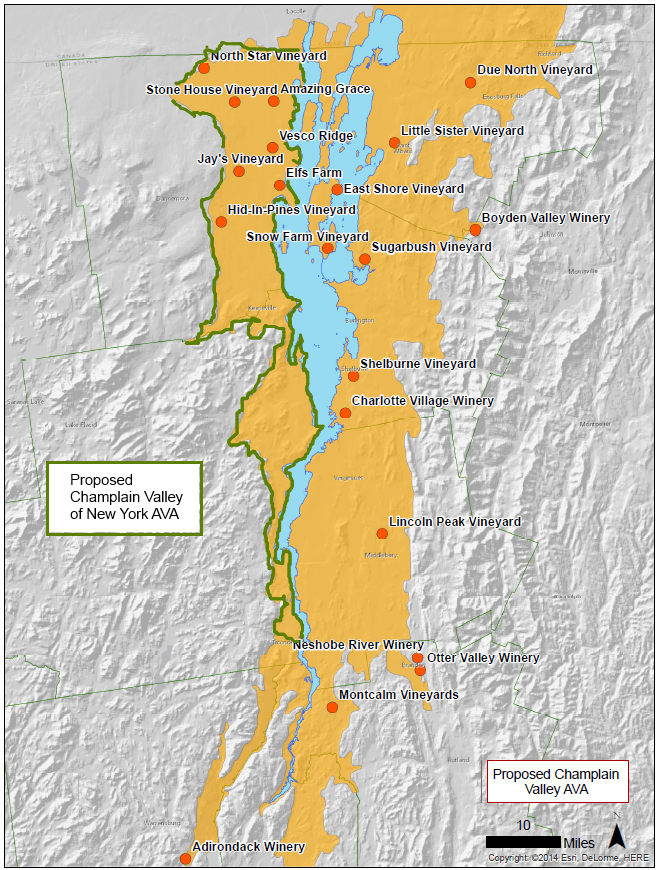

Producers way upstate have worked together and an AVA application has been submitted to define an area specifically comprised of the “Champlain Valley of New York”. Having been accepted for review, the petition is moving through a process that will result in a decision within a year or so.

An alphabet soup of designations delineate European wine growing areas such as the AOCs of France, DOCG wines of Italy, or the DAC of Austria. With each comes a set of rules and regulations that can control all aspects of winemaking through constraints on vineyard boundaries, grape varieties, ripeness levels, barrel aging and approval by quality control panels. Here in the US, AVA rules are a bit simpler and are targeted to define wine with 85% of grapes coming from within a precise geographical boundary. That geo-map has to meet three criteria:

- Show evidence that the name of the proposed new AVA is a locally or nationally recognized term for the area;

- Prove through historical or current evidence that the boundaries are legitimate;

- Provide evidence that growing conditions such as climate, soil, elevation, and physiology are distinctive;

Colin Reed of the Champlain Wine Company in Plattsburgh, NY — who submitted the final version of the application — wrote and told us that the region was defined as running:

“… from the Quebec border to Ticonderoga North to South, and the slopes of the Adirondacks to Lake Champlain East to West. This is an area unique in the combination of soils that once formed the bed of ancient Lake Vermont and the climate of the leeward side of the Adirondacks, without the benefit of the moderating influence of westerly winds over Lake Champlain that causes the Vermont shores to be a bit warmer than our side of the Lake.”

There are already several active vineyards and wineries in the area. More acres are currently being turned to vines or are in the planning stages, while untapped viticultural opportunities are still yet to be unidentified. They say that anywhere you can grow apples, you can grow the cold hardy wine grapes, so given the huge production of the former in these parts, a potential increase the latter could certainly be expected.

Regional interests in such designations are not limited to the Adirondack Coast of New York. There is a strong feeling among a number of cold climate folks that an AVA is an important part of getting on the domestic wine map, and that sub-AVAs can help producers appeal to the different liquor laws in New York and Vermont. A couple of years ago a petition was floated for the Champlain Islands of Vermont, but for technical reasons that application did not go through, and is still undergoing revision and review by the applicants.

Also promising, are the intentions of the Lake Champlain Basin Program, who we previously covered in their effort to help establish an International Wine Trail connecting Upstate New York, Vermont and the wine country of Quebec. The Basin Program is in the early stages of pursuing an AVA that would contain the entire Lake Champlain Valley watershed. They have already organized a series of meetings with stakeholders that include wineries, tourist bureaus and chambers of commerce to gather support for the project, and the interest among participants is evident.

Whether or not AVA designation really does have a positive effect on a region’s recognition, is a continuing debate. Some wonder if there has been too large a proliferation of AVA and sub AVA such as to dilute the worth. Others stand by the need for a distinguishing factor to help consumers make their decision, especially if there is a portion of wine in the market being made with fruit from other regions. Others firmly believe that the difference can be tasted in the wine.

I’ve had La Crescent from Vermont, Minnesota, Wisconsin and three different regions of New York, and I can certainly say that they were distinctly different, but I’ve not had enough from any one region to lead me to believe that there a common thread within. But that is the point of the AVA…to say that the wine is from “this place” and not another, it does not imply any homogeneous trait in the neighborhood. What an AVA certainly does mean, is that a new level of expectation for both producers and their customers will be attained, and it’s a good sign that unique things are growing.