It wasn’t yet midnight, but it was long past sunset in the peat marsh. Two men who looked like deep-sea divers were prepared to use their wetsuits for a new purpose: they would be diving for peat. The decayed vegetation is an attractive part of the process of making single-malt whiskey — it’s smoked, adding a classic aromatic texture the likes of which can be found in Lagavulin and Laphroaig — but there’s one problem. The New York State Department of Environmental Conversation protects the marshlands, so the peat can’t be extracted legally. That’s why the men were prepared to obtain it under the cover of night.

The preceding paragraph is only an idea, for now. But don’t think the ambitious minds behind the Hudson Valley’s Hillrock Estate Distillery haven’t thought about it.

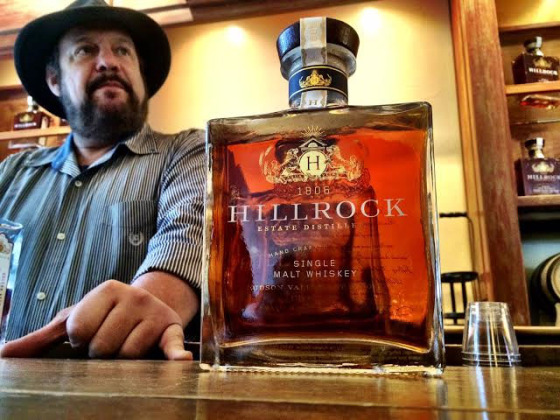

“The local peat tends to be in the DEC wetlands,” said Jeffrey Baker, the owner and financial muscle leading the remarkable new facility. “We want to stay above board.”

That’s the last hurdle, it would seem, in the hunt for single-malt terroir.

The notion of terroir tends to live in the wine world, where enthusiasts debate the impact of soil, place, and more. Baker is convinced that there is terroir in whiskey, and to show it, he constructed the only purpose-built malthouse at a distillery in the country. It’s a throwback. Baker studied malthouses in the United Kingdom and decided to create what have been called, in 17th-century Europe, a “one-man malthouse.” On your visit, you’ll see the grain on the floor, but you’ll want to resist the urge to pick it up or lay down and do grain angels. “That’s $60,000 worth of whiskey on the floor,” Baker explained. The grain will stay on the floor of the malthouse for three days; it needs to be aerated every six-to-eight hours, which is what the crew was doing when we visited. After three days, the grain slides through the floor hatch and down into the kiln. It’s on its way, part of the process now celebrated as “field to glass.”

On your visit, you’ll see the grain on the floor, but you’ll want to resist the urge to pick it up or lay down and do grain angels. “That’s $60,000 worth of whiskey on the floor,” Baker explained. The grain will stay on the floor of the malthouse for three days; it needs to be aerated every six-to-eight hours, which is what the crew was doing when we visited. After three days, the grain slides through the floor hatch and down into the kiln. It’s on its way, part of the process now celebrated as “field to glass.”

Most Scotch is aged in used Bourbon barrels for at least six years. Hillrock puts 80% of their production away for longer-term aging, but they’ve created a shortcut for the rest: by using smaller barrels, Baker thinks he can achieve the same effect in less than three years.

The Hillrock team has considered every detail, from the barrels, to the barley fields rolling off the hills, to the view of the distant Berkshires. Baker proudly pointed to the land he bought in 1999 and said, “The water is different here. That might be the most significant factor. The grain is going to pick up different characteristics here. The grain won’t be the same here that it is in Scotland.”

If Baker chose the land and equipment carefully, he made the obvious choice in his Master Distiller. Well, it was only obvious if he could convince Dave Pickerell to take the job. The notion of searching for terroir in American whiskey was appealing to Pickerell, who has become an industry titan. He worked as the Master Distiller for Makers Mark, earning respect across the distilling world.

“Our fields write their name in clove and cinnamon,” Pickerell said when our group visited the tasting room. “We knew it the first batch. There were contractors hammering nails in, and everyone stopped. Everyone knew, before we even had everything built. This is what terroir is in whiskey.”

Pickerell is not only a highly regarded distiller; he is a master entertainer when he’s in front of a crowd. Gesturing for emphasis, he declared that there were only three differences between Hillrock’s peat-smoked single malt and Scotch.

“One, we’re not in Scotland,” he said. “Two, the law says the barrels must be new here. And three, we don’t add caramel coloring. That’s it.”

When the group fell silent to taste the whiskey, Pickerell announced, “We do have a smoke bomb coming.” By that he means: the current single-malt includes eight hours of peat smoking. Hillrock will soon release a single-malt with 20 hours of peat smoking. Ask Pickerell what he thinks and he doesn’t need to say anything; his eyes go wide and his mouth curls into a broad smile.

Eventually there will be a fourth difference between Hillrock and Scotch: the peat. Hillrock continues to bring in peat from Scotland a couple pallets at a time, as needed. Baker is patient, but eager to learn what Hudson Valley peat will do to his product.

“The local peat will taste different,” he said. “Remember that a lot of the peat in Scotland has seaweed, which gives it an iodine, salty flavor. We won’t have that here. It will be interesting.”

Hillrock makes one 30-gallon barrel per day. By comparison, Makers Mark produces roughly 2,000 barrels per day. That leaves Hillrock with the relatively small production of 60,000 bottles annually. For now, most of the Hillrock allocation goes to northeast markets. Eventually, Baker expects to hit the west coast, then Europe.

The single-malt sells for $100. Baker knows that customers can find Scotch for less, but he expects the quality to compete. Hillrock also offers what might be the only true solera-aged American whiskey, retailing for $80. A double-cask rye goes for $90; the George Washington rye fetches $50. Even a Hillrock hat is $32, exceeding the market rate without the terroir.

But a visit to Hillrock seems to melt the concerns over the price tags. The quality is unimpeachable, the aromas addictive. Terroir in whiskey? Come to Hillrock a cynic, you might leave with an open mind.

“Just as pinot noir is not the same in Burgundy as it is in Napa Valley, we’ll offer something different, something that is our own,” Baker said to a room filled with writers and critics. They are accustomed to rolling their eyes, but on this day, no one seemed to be doubting him.